No importance in being Ernest

In the latest in his series on eminent Victorians, Neil Titley turns his attention to the poet Ernest Dowson

Friday, 16th January — By Neil Titley

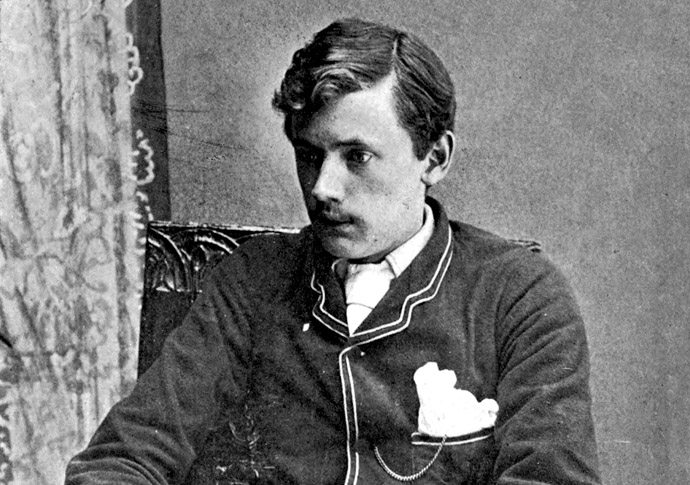

Ernest Dowson

SUCH was the fame of the Cheshire Cheese’s parrot “Polly” that news of her death 100 years ago was broadcast by the BBC. Other renowned habitués of the Fleet Street tavern have included Dr Samuel Johnson, Charles Dickens, and PG Wodehouse, all of whom also received fulsome obituaries.

However, one of the pub’s most regular of regulars died in almost total obscurity.

Described by TS Eliot as “the most gifted and technically perfect poet of his age”, the verse of Ernest Dowson (1867-1900) provided Hollywood with two of its most famous film titles: Days of Wine and Roses and Gone with the Wind.

But, despite his brilliance as a bard, his life was one of almost unmitigated disaster.

Having left Oxford in 1888 without a degree, for a short time he helped to manage his family docking business in the East End. He soon drifted into the more congenial company of the Cheshire Cheese and the 1890s Decadent movement.

Whereas most Decadents to some extent posed as “tipplers and whoremongers”, Dowson flung himself whole-heartedly into the role.

After his drinking bouts, Dowson often appeared in the morning with a cauliflower ear and once with stab wounds in his forehead. He took to carrying a small revolver that he had won in a card game.

He was arrested so often for “drunk and disorderly conduct” that the magistrate used to greet him in the dock with: “What, you here again, Mr Dowson?”

After his conversion to Roman Catholicism, Dowson acquired the habit of dipping a small crucifix into his wine before drinking. It had no visible effect on his decline. WB Yeats reported seeing him “pouring out a glass of whisky for himself in an empty corner of my room and murmuring over and over in what seemed an automatic apology: ‘the first today, the first today’.”

Oscar Wilde dismissed attacks on Dowson saying: “If he didn’t drink, he would be somebody else. You must accept a person for what he is. It is not regrettable that a poet is drunk, but that drunks aren’t always poets”.

Dowson encompassed his own ruin when in 1891 he fell deeply and permanently in love with a 12-year-old girl called Adelaide Foltinowicz, known as “Missie.” He met her when she served him in her parents’ restaurant The Poland in Sherwood Street, Soho. As a result, he committed himself to years of dining every evening in this shabby café simply to observe Missie. Despite his obsession, Dowson realised the absurdity of his position – “the veal cutlet and the dingy green walls of my Eden”.

While deeply shocking to current morality, during the Victorian age the general population took a more relaxed attitude to sex at an early age. In England between 1851 and 1881 children under 15 outnumbered adults and, given the high rate of infant mortality, girls were encouraged to marry young in the hope of raising as many offspring as possible. Until 1885 the UK age of consent was 12; in most of the United States it was 10 – in Delaware, seven.

Dowson never took advantage of his young waitress. “I swear there never was a man more fanatically opposed to the corruption of innocence than I am.”

But while the innocent might be safe, he had little compunction about the more experienced.

He was said to have picked up a different sex worker virtually every night.

Yeats observed: “Dowson sober would not look at a woman; did he not belong to the restaurant-keeper’s daughter? But, drunk, any woman, dirty or clean, served his purpose.”

His friend, the equally alcoholic Lionel Johnson, made an inept attempt to wean Dowson off his addiction to prostitutes. As the pair staggered along Oxford Street Dowson announced: “I’m going to the East End to have a ten-penny whore”. Johnson, in an attempt to restrain his friend, had tried to prevent his departure: “No, no, Ernest! Have some more absinthe!”

In 1897 in need of a respite from London life, Dowson retreated to Dieppe in France, where he encountered his old acquaintance, the now-disgraced Oscar Wilde. In a truly weird episode, Dowson attempted to expand Wilde’s sexual horizons by inviting him to the local brothel.

Oscar agreed and was accompanied to the door by Dowson and a cheering crowd who waited until Oscar emerged. The experience did not alter Oscar’s homosexual tastes: “It has been the first time for 10 years and it will be the last. But do spread the story all over England. It should entirely restore my reputation.”

On his return to London Dowson discovered that his beloved Missie had married someone else. The news destroyed him.

Frank Harris remarked: “When she chucked him for some tailor, the wound served, and Dowson died of it.”

By 1900 he had lost his family, any semblance of regular income, and all his teeth, while gaining tuberculosis and a skin disease. Unable to pay the rent even in a Euston Road dosshouse, he was rescued by a friend and taken away to die in Catford.

Yeats summed up his life: “I cannot imagine a world in which Dowson would have succeeded”.

• Adapted from Neil Titley’s book The Oscar Wilde World of Gossip, available at Daunts, South End Green. See www.wildetheatre.co.uk