Drawn to the future: when sci-fi comic book artists were given a free hand

Dan Carrier visits the Cartoon Museum for a glimpse of the future while looking at the past

Friday, 16th January — By Dan Carrier

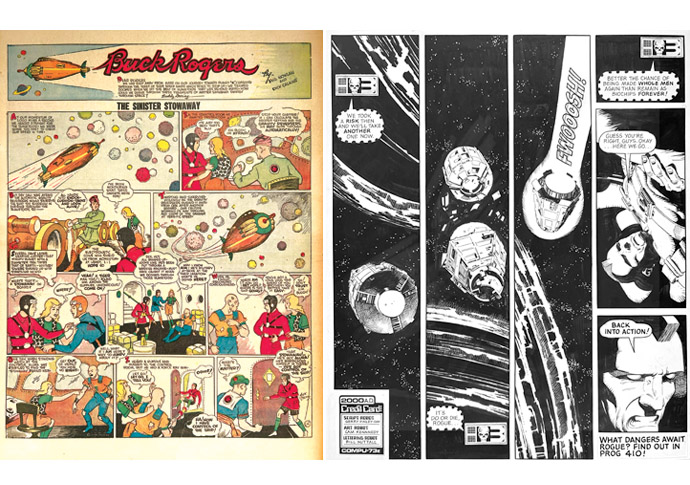

Left: Buck Rogers; right: Rogue Trooper [© Rebellion Developments Ltd]

THEY are words an artist must just love to hear – there are no budget limitations and you create whatever you want, and on whatever scale you want. The only shackles are your imagination.

This isn’t a fantasy pitch from a collector or commissioner – just what comic book artists writing sci-fiction could enjoy as they sat at their drawing boards and worked out story lines.

And an exhibition at the Cartoon Museum, in Well Street, Fitzrovia, illustrates how the creators of seminal sci-fi had carte blanche to let their imaginations run riot – no matter how big the idea.

Museum curator Hannah Whyte has played a key role putting together The Future Was Then.

“With comics, you are drawing on a page and your budget is essentially limitless – unlike TV and film, where the costs of creating a massive spaceship might be prohibitive,” she says.

“If you can draw it, you can make it happen.”

Tackling the huge range of sci-fi that has graced comics over decades gave the show a wide starting point: it contains 80 illustrations and tells us something about how people viewed times to come, as well as shedding light on the mores, likes and fears of an era.

“Sci-fi is present throughout comics and cartoons – the artists featured love the idea of life in the future,” adds Hannah.

Because of the links between cartoons and sci-fi, Dan Dare, Buck Rogers and Judge Dredd have become global household names – and the museum has an impressive breadth of work to choose from.

“We have a lot of incredible sci-fi,” explains Hannah. “And we have been in conversation with artists and lenders for the exhibition. It has enabled us to tie together different examples and consider what stories we could tell through this art work?”

Stories by Jules Verne and HG Wells are considered somehow prophetic, and George Orwell’s novels Nineteen Eighty-Four and Animal Farm illustrate, storytelling using analogies, parody and soothsaying: these have always been popular. Sci-fi comics played the same role, says Hannah.

“Many comics from the past are set in the future – and we asked the question in the show – what came true? If you look at a series like Judge Dredd, with mega cities, authoritarianism – it happens a lot where comic artists are making a comment about the present. It means in some cases they can feel very predictive.”

She cites a story called Undiscovered Country, which was released before the Covid-19 pandemic and feels prescient today.

“It is set in a near future, a world where the US has isolated itself,” says Hannah. “And part of the plot involves a global pandemic – and this was written before Covid.”

The plot features a nation that was once the USA, a place now shrouded in mystery after sealing itself off from the rest of the world 30 years previously. When a pandemic hits, scientists travel to the nation in the hope of finding a cure.

Others were little less successful in their portrayal of future worlds.

“Then you have Dan Dare, which was written in the 1950s and set in the 1990s,” she adds. “It still feels very post-war, and doesn’t feel like the 1990s we know of.”

It shows how sci-fi is also a reflection of the times in which they were created.

“When these stories are being told about imagined futures, it is of course impossible for the writers and illustrators not to be influenced by the present world around them,” she says. “In the 1930s and 1940s, we see these really excited comics about space travel and star-faring. It is almost Utopian – and then they become more dystopian, influenced by the world war.”

The archive allows the changes and development of visual art to be traced. And it also shows the breadth the medium offers. “You can see the links between generations of comics. But the wonderful thing is it is so open, so even today you can look at a whole exhibition of artists working and they will all be totally different,” she says.

“There is great variety. You can see the trends in art and how they are influenced by the world around them. Dan Dare has a 1950s, conservative look, while Tank Girl, produced in the 1900s, is undeniably from the Brit Pop era.”

Hannah’s relationship with comics began, as it did for many of us, at an early age. “I was a big comic book fan – I love all things related to comics, illustration, art… and I did an art degree at university,” she adds. “I loved all sorts of comics – I was a big Beano fan, of course, and working at the Museum means I get to see comics and cartoons from such a range of eras – including my childhood and adulthood.”

These include everything from the 1960s counter culture illustrated though the American publication Underground Comix to early works.

“My favourite character is Krazy Kat,” she says, the creation of artist George Herriman, which began as a newspaper strip in 1913.

Hannah began at the museum working front of house and then on exhibitions. She had spells curating elsewhere, including a time with the art of the great Highgate-based illustrator, W Heath Robinson.

“I am involved in curating the collections we have on-site – and we have an amazing collection of historic cartoons and art work,” she says.

“Sometimes people get in touch if they work with a historic relevance. Cartoons are a lovely medium, responding to events in the news – it is art that is created quickly.”

The museum has a collection of over 6,000 original cartoons and a library of over 8,000 comics and books.

“The collection stretches back from the 18th century to the present day,” she adds.

She has a personal favourite in the guise of the works of Richard Newton, who worked in the 1700s. He created art that highlighted the evils of slavery, took aim at Napoleon and chronicled the mores of fashionable London. He became well known despite dying aged just 21 in 1798.

“He was such a cheeky cartoonist – he poked fun at the royals and politicians, drawing them with their bums hanging out,” Hannah says.

“Cartoons have always produced controversial work and the archive is packed with interesting things.”

• The Future Was Then is at the Cartoon Museum until March 21

www.cartoonmuseum.org