‘The town is simply disguised countryside’

Dan Carrier revisits historian Gillian Tindall’s engrossing history of Kentish Town, following her death last week

Friday, 10th October 2025 — By Dan Carrier

Gillian Tindall, author of The Fields Beneath, above left, who died last week

IT was while roaming around the back streets of Kentish Town in the early 1970s that historian Gillian Tindall saw a legend etched above a door.

The house the door belonged to was one of a row in a Victorian terrace, earmarked for a slum clearance project, and was providing a temporary, squatted home to those in need.

“I saw that over the lintel of one of them, someone had carefully carved an inscription: the letters, cut through the sooty surface into the fresh yellow brick beneath below, stood out clearly – ‘The Fields Lie Sleeping Underneath’,” she would recall.

This line, said Gillian, was “deeply satisfying,” as she had come “unexpectedly face to face with your own private vision”.

Gillian, who died last week aged 87, would write how she had been exploring London, aware of the land lying beneath the sprawl of human impact.

“The town is simply disguised countryside,” she would say. “Main roads, some older than history itself, still bend to avoid long-dried marshes, or veer off at an angle where the wall of a manor house once stood…”

From this starting point came Gillian’s book, The Fields Beneath: The History of one London Village.

As well as telling the story of Kentish Town, it reflected a new interest in social history, an example of how the study of one place could be extrapolated to be a bellwether of historic change. The book remains both a beautiful read and a telling document about the causes and effects of urban evolution.

In TFB, Gillian walks us from the days of a smallholding near a well-used path out of London to an urban centre today. She finds clues and pointers that explain the Kentish Town we experience now.

“Kentish Town is, for the historian, comparatively untouched,” she said in 1977. “It is, to use an archaeological metaphor, like a dig on a new site.”

1960s ‘improvements’ – pre-Victorian shops amid rebuilding and a tower block in Monmouth Street

She starts the book with the line: “In the beginning there was the road. But before the road, there was the river…”

Kentish Town of Norman times “consisted mainly of forest, infested by outlaws, robbers and beasts of prey. Today, the remains of this great Middlesex forest can be found at Kenwood and Highgate Wood.”

The Fleet flowed from the Hampstead hills down to the Thames, and good agricultural land saw pastures produce feed for livestock.

She reflects on how Kentish Town was used by commuters in the 17th century, telling the story of an actor called Clun. He had been appearing in a play, The Alchemist, in 1664 when he was the victim of a robbery: Samuel Pepys records in his diary how Clun was returning home to Kentish Town on horseback after a show when he was set on by footpads: he fought back, was bound and stabbed and left to die in a ditch.

“Pepys, with his usual inquisitiveness, went to view the scene of the crime and also learnt from London gossip that Clun had been drinking with his mistress in town before going home, which is why he was riding so late.

“It will be noticed that what the unlucky Clun was doing was commuting”, she adds.

“He worked in the centre of London, but, despite having a mistress there, returned to Kentish Town apparently every night. This was a relatively new concept in 1664, and may point to some improvement in the condition of the roads since the beginning of the century, when mainly retired persons had taken homes in Kentish Town. Pepys himself found the place convenient enough for brief drives to take the air.”

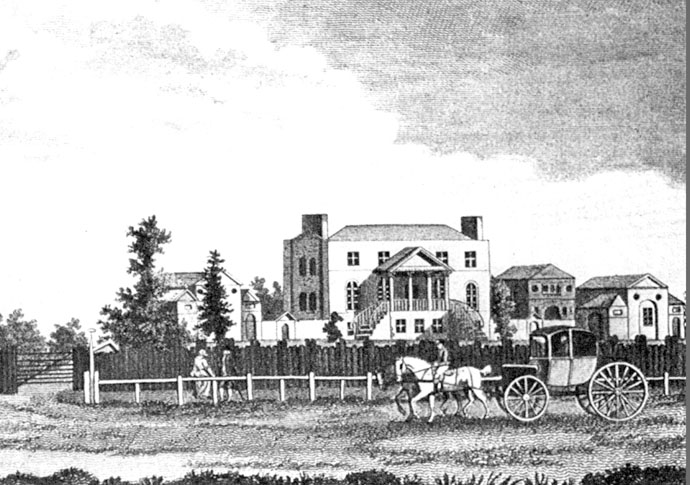

One of the few surviving examples of the kind of gentleman’s houses still being built in Kentish Town in the 1820s and 1830s

A minor building boom in the 16th and 17th centuries created a rural retreat – one that would be quickly consumed by the Victorians.

“The truly cataclysmic change came in the 1840s, 50s and 60s, when pastures and market gardens that had been the backland to the High Road were covered inexorably, field after field with terraces of houses,” she writes.

“This was followed by the coming of a mainline railway, which bisected the district and destroyed, for the next 100 years, most of the pretensions to prettiness and gentility.”

The railways brought soot and dirt and noise, and that corresponded with the perception of the area as a low, dingy place to live.

Later she reflects how, in the mid-20th century, a new trend emerged.

There was an accepted wisdom that when homes were built they were desirable, but over successive generations the homes would deteriorate until they had reached a point beyond repair – and then the local authority could afford to issue compulsory purchase offers and sweep whole streets away.

But this cycle of build / deteriorate / knock down / replace did not take into account the issue that created the modern Kentish Town – the clanking, noxious railway lines.

“House property was a wasting asset, as the descendants of Victorian property speculative builders would tell one another sadly creeping round unmodernised properties for which they could only ask minimal rents,” she said.

“The truth must surely be that, between the later 19th century and the 1950s, the disadvantages of the old inner areas were marked enough to outweigh the advantages.

‘Bateman’s Folly’ at the foot of Highgate West Hill – by building it, complete with ornamental water gardens, its owner bankrupted himself

“An important consideration was, simply, the dirt of life near the centre.

“We tend to forget – and many people approaching adulthood have never known – the sheer filth of London in the days when every household was warmed by one or more coalfires and all the trains were steam.

“It is surely no coincidence that these districts began to appeal again to middle classes around 1960, precisely at the time when the steam trains were being withdrawn for good and when the clean air legislation that followed the ‘smog’ scare of the late 1950s was beginning to have a real impact on people’s heating arrangements.”

At the same time, councils like Camden were hoping to build housing to replace Victorian terraces.

It means TFB feels like an explanatory stepping stone, published when the impact of housing policy in the “Brave New World” was reshaping NW5.

“Highly permissive legislation existed to enable councils to acquire properties to carry out ‘improvements’,” she noted.

“What the legislators did not realise was the extent to which this power would presently be abused by councils to carry out grandiose schemes that owed more to the visions of le Corbusier than to the real needs and wants of the population of urban areas.”

Such schemes saw swathes of Kentish Town and Gospel Oak demolished, with the outside loo and tin bath consigned to the past.

But Gillian looked beyond the vote-winning promises. “What no one admitted until well into the 1960s, when whole communities had been destroyed and large tracts of once-living urban landscape had been turned into deserts of windy concrete towers set on useless doilies of ownerless grass, was that… so much so-called slum clearance has been no more than a form of conspicuous consumption and political self-advertisement,” she reflects.

“Slum clearance was so well established that, like a blind monster, it went nosing around for more.”

She pointed out that there was nothing like declaring an area a slum to create a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Her pen hovered over the changes in recent times. The 1944 London Plan called Kentish Town “an area in need of removal… an inchoate community… peppered with small industries”.

As Gillian points out, this was not a sign of sickness but of a viable community: “Kentish Town did not have industries that created a lot of noise or smell: the remnants of the piano trade remained, mews, now empty of horses, became car repair workshops… nooks and corners contained many small workshops that made envelopes, boxes, wire gadgets, toys, patent medicines”.

The Fields Beneath remains in print, 48 years after it was first released. It is both an encyclopedic consideration of one village’s story and a fortune teller’s ball, projecting an image of Kentish Town of today. Above all, TFB is thoroughly enjoyable and accessible, with Gillian’s wit and intelligence glowing on every page.