Site seer: how novel captures the variety of Caribbean British experience

Friday, 7th November 2025 — By Maggie Gruner

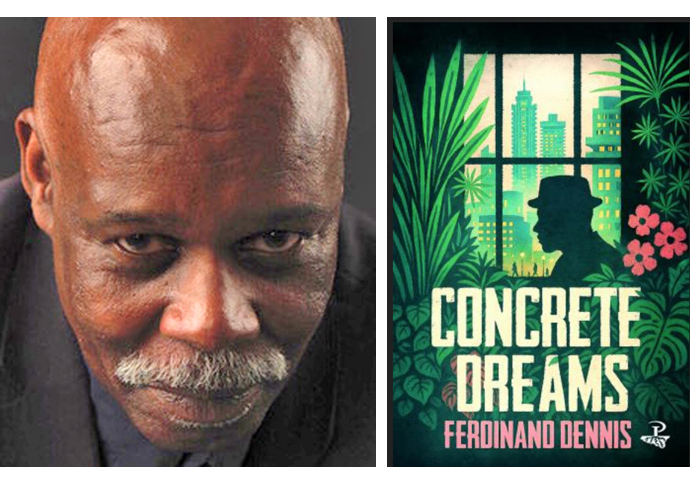

Ferdinand Dennis, and Concrete Dreams, his compelling new novel [Thomas Stewart]

JAMAICAN immigrant Lucas Bostock has been warned by others on the street about racist attacks, and is walking via an alternative route when he sees a man covered in blood.

Concrete Dreams, the compelling new novel by Finsbury Park writer Ferdinand Dennis, relates how Lucas holds the wounded Caribbean man’s throat to prevent him bleeding to death while he is being taken to St Mary’s Hospital, Paddington.

Lucas is shaken, but undaunted. He is the ambitious patriarch in the novel, a London-Jamaican family saga. Arriving in 1950s London, he is determined to succeed. The story, with Lucas and his family at its heart, captures the variety of Caribbean British experience.

Racism is part of the background to the lives of the novel’s inhabitants, but award-winning writer Ferdinand insists: “My characters are not victims.”

Born in Jamaica, Ferdinand came to London in 1964, aged eight, and grew up in North Paddington. He told Review his Jamaican carpenter father’s “work ethic, ambition, the pride he took in his work and the skill he had” inspired creation of fictional Lucas, who works on building sites, as a carpenter, buys property and becomes a landlord.

Lucas’s wife, Rhoda, thinks he’s insensitive and hard as concrete. He’s also a philanderer. Rhoda leaves him, regretfully able to take only their daughter, Maureen, with her. Strict disciplinarian Lucas raises their three sons.

Set against a backdrop including Camden, Finsbury Park, Archway and Stoke Newington, the story runs from the 1950s to the late 1990s, unfolding the lives, loves, secrets, aspirations and struggles of the Bostock family, their friends, relatives and Lucas’s Caribbean tenants. The story’s “narrator” is no disembodied voice, but a physical presence in the novel, struggling to deal with his noisy, sometimes intimidating young male neighbour.

The story explores race, masculinity, family relationships, changes in London and society. Dennis said he wanted to contribute to the “body of literature about Caribbean migration to this country post the Second World War, and somehow fill in gaps I perceived. All of us have stories to tell, and I could never quite see my experience of the various communities that I’m familiar with reflected in the books that I’d read.”

In the mid-1970s, when Lucas and Rhoda’s youthful son Samuel jogs in Finsbury Park, he gives race “little thought”. But later he mocks younger brother Vincent’s teenage dream of becoming prime minister, saying he’s a black man in a white country and the path will be blocked. Ironically, years later Samuel becomes a Labour councillor and sets his sights on becoming an MP.

Maureen insists to herself she is just a person, an individual, but the cumulative effect of small racist incidents and remarks leads her to the “startling discovery” that she is black. “I don’t think her awareness becomes an impediment to her life,” Ferdinand said. “She will survive and prevail.”

He has “horrific memories” of his primary school playground and names he was called, but feels London is now “at ease with its multicultural nature and diverse population and cultures, and takes pride in that.”

In 1984 Vincent notes a different mood in London, more black faces on television, a new Black newspaper. Even the music has changed, from the “lamentation” of Rastafarian reggae to assertive urban music of rap or hip-hop.

Although born in the capital, Vincent feels he’s still a sort of immigrant, his roots in the city shallow. Dennis knows that feeling, but thinks that today there are “young black Brits who feel very secure in their black Britishness.”

He crafts his characters with consummate skill and vividly evokes places: a derelict house in Stoke Newington that Lucas buys in the 1950s and renovates for his family, and for letting rooms to tenants; the Jamaica of Lucas and Rhoda’s memory; Finsbury Park and the neighbourhood’s streets, shops and cafes.

At a Caribbean restaurant in Camden Town, Lucas, about to return to Jamaica, meets his three adult sons for a farewell dinner – and hopes, in vain, that Maureen will show up. When Samuel says their childhood “lacked rituals”, Lucas’s spiky response epitomises his viewpoint: “Son, me give you food, me give you clothes, me give you shelter.” He says he gave them drive and ambition and their mother would have drowned them in love, but love is “not enough.”

The novel explores the effects of Lucas’s legacy as his children build their lives.

Neville becomes a boxer, and later a church pastor. Samuel pursues his political career; Vincent is a journalist. Maureen becomes a store manager.

Lucas is accused of lacking compassion, but Vincent and Maureen are chinks in his armour. Vincent, feeling estranged from his family and missing his daughter, is “in pain,” says Lucas. Baffled by Maureen’s absence at the farewell meal, he later reads a note from her, saying “Unforgiven, unforgivable, unmissed.” Lucas admits he has “lived mean.” But, in his loneliness, it’s hard not to feel sympathy for him.

The narrator’s personal story brings an intriguing ultimate twist to the multilayered novel, which leaves its characters lingering in the mind long after the final page is read.

• Concrete Dreams. By Ferdinand Dennis, Peepal Tree Press, £14.99

Jamaica’s disaster relief

AS Jamaica reels from the effects of Hurricane Melissa, Ferdinand Dennis’s family and friends on the island are safe in Kingston. Others haven’t been so lucky. If you want to donate to help with disaster relief, see details at Support Jamaica’s official disaster relief and recovery portal and their donation page at: https://supportjamaica.gov.jm