Rocket man

Remember, remember... Dan Carrier lights the blue touch paper and retires to learn the history of fireworks

Thursday, 7th November 2024 — By Dan Carrier

New Year’s Eve celebrations in London [SIMarsden/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0]

THE Brock family were famous for lighting up night skies. The fireworks dynasty was a household name, so it was no surprise that when, in 1921, Arthur Brock contacted authorities with an experiment that involved fireworks, they were eager to listen.

Brock laid out several tons of fireworks around the summit of Parliament Hill. His aim was not to entertain Londoners, but to see if launching a serious amount of gunpowder into the skies could cause rain to fall. Journalists noted after a short period that large rain clouds did indeed form – but not a drop fell.

Such vignettes fizz and sparkle across the pages of John Withington’s latest book, a comprehensive history of the firework.

This is his 11th: his background is in broadcast journalism. As an author, many of his works have had a focus on disaster: and when dealing with the dangers of fireworks, tragedy stalks the pages of this wonderful story of a substance that has lit up human existence, sometimes for good, often for worse.

He recalls how fireworks marked his Mancunian childhood – “I have no recollection of seeing them at private celebrations or even on New Year’s Eve,” he writes. “They made an appearance in October, a couple of weeks before the great day, in newsagents, sold singly or in selection boxes.”

As many will fondly recall – or not-so-fondly, depending on what end of the banger you were standing – there was a huge selection of little squibs one could easily buy and then terrorise neighbours with.

“Bangers were a penny each and gloried in names like Little Devil,” he adds. “Their sharp reports would puncture the days running up to November 5 as boys threw them in the street. Especially intimidating were rip-raps, which looked like tightly folded little snakes and gave a bang every few seconds, flying off each time in random directions at ankle height. My mother thought they were a waste of money and made sure our hard-earned cash was invested in more picturesque fireworks.”

There’s a good chance the fireworks John’s parents let off were made by one of the UKs family firms, household names such as Brocks or Pains.

John shares the stories behind some of these names that had provided many oohs and ahhhs.

John Brock founded his company in Islington in 1698. The thrill creator sadly died at the hands of his product in 1720: a huge explosion destroyed his factory. It also killed his daughter.

The family were not put off and became a leading brand, as well as the inventors of the annual public displays at Crystal Palace, which they set up in 1865.

The Victorians loved a firework, made by many a cottage producer. One such character was Joseph Wells, a Thames lighterman – a job that would have involved using pyrotechnics and flares. He advertised his skill as a “public decorator”, available for festivities, and in 1875 his Roman Candle won “Best in Show” at Alexandra Palace.

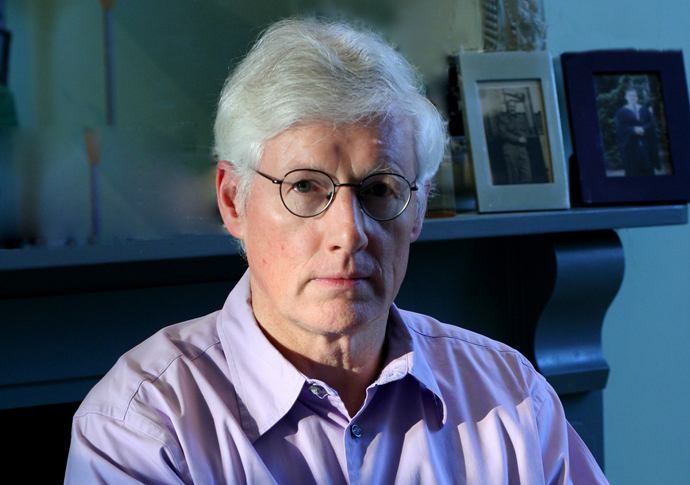

John Withington

Other names that remain today include Standard Fireworks, dating from 1812. The firm began in Huddersfield, founded by a draper, William Greenhalgh, who produced his own fireworks in the run up to Bonfire Night.

The author gives us chapter and verse over the UK’s relationship with the firework, which was encouraged by a law marking November 5th.

But, of course, the firework has a history stretching back to ancient China.

The Chinese were the first to make the most of gunpowder. There was already a culture of using firecrackers made out of bamboo to scare away wild animals and to entertain. Because a bamboo shoot is split into compartments, when heated, the air expands and explodes. By the 12th century, gunpowder was being packed into these chambers and set off to great effect.

At some point more than 1,000 years ago, the Chinese mixed sulphur with charcoal and potassium nitrate to create the explosive substance. The nitrate, also known as saltpetre, was believed to have magical, life-giving properties.

Their experiments led to military applications: developments included arrows moving from carrying an explosive charge as a primitive warhead to gunpowder becoming a form of propulsion. The invention of the rocket brought both fear and wonder, as a rocket could share an aesthetic and temporary beauty with many people.

For others, it led to big dreams – and tragedy.

John tells the story of Chinese official Wan-Hu, who saw rockets as the means to send him into the heavens – a far-sighted idea, but one with safety questions Wan-Hu seems to have ignored.

“He sat in a chair equipped with two kites and powered by 47 rockets,” explains John.

“The 47 assistants lit the 47 fuses and retired smartly. There was a huge explosion, and when the smoke cleared, there was no sign of the chair or Wan-Hu.”

He goes on to point out that the translation of the name of the man who was blasted upwards, never to re-appear, is Crazy Fox.

When gunpowder reached Europe is shrouded in “much historical smoke”. John traces how fireworks made their way west – they were commonly used in India for festivities as well as fighting from the 1300s – and reached the UK by the time Henry VII married Elizabeth of York in 1487.

A flotilla of boats headed up the Thames, with the Lord Mayor’s barge decked with a fire-breathing dragon at the helm. Dragons were a regular occurrence in such pageants. When Henry VIII married Anne Boleyn in 1533, London was treated to a plethora of fire-spouting lizards.

Fireworks were used to illustrate the might of the monarchs across Europe, employed to jazz up festivities, coronations, weddings and military triumphs. The technicians behind these shows were treated like rock stars, well paid and poached by one royal household from another.

It is no surprise, considering her love of pomp and circumstance, that fireworks were ubiquitous throughout the reign of Elizabeth I. They were well employed in the playhouses, Shakespeare’s stage directions included pyrotechnics. The author walks the reader through the ways they were employed in Elizabethan theatre – creating a wonderful image of delight in a world where moving images were unknown and a firework was considered truly wondrous.

It was when Elizabeth’s successor James I took to the throne that our relationship with fireworks would become an event in the calender.

The Gunpowder Plot, which saw a group of Catholic families employ the mercenary soldier Guido Fawkes to blow up Parliament, meant November 5th would not be forgotten, and noting the deliverance of the king from a fiery end was written into the statute book. It was often used as an excuse for violent anti-Papal demonstrations, and other rowdiness. It became a day of rebellion.

Fireworks were used to draw in the crowds to London’s pleasure gardens, while by the 20th century, at either ends of the capital, two palaces fought for the reputation as the greatest show – Alexandra in the north and Crystal in the south.

This comprehensive tome lights up a fascinating topic, and understanding the history of fireworks adds to the joy of watching a night sky light up this week.

• A History of Fireworks From Their Origins to the Present Day. By John Withington, Reaktion Books, £25