Review: The Burning Question

In his new book, Andrew Gilmour shows how the climate crisis fuels conflict which in turn ramps up the climate crisis

Thursday, 13th November 2025 — By Dan Carrier

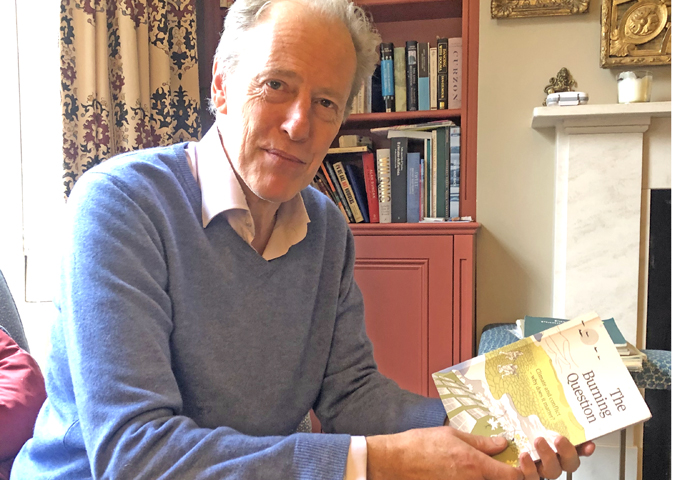

Andrew Gilmour, executive director of the Berghof Foundation

It is a perfect storm. War creates vast amounts of polluting, climate-warming gases – and the climate crisis in turn creates conditions for more conflict.

In a new book by Andrew Gilmour, he calmly lays out how a vicious circle means climate change drives conflict and conflict in turn drives climate change.

Camden Town-based Andrew is the executive director of the Berghof Foundation, which looks at conflict resolutions around the globe. He spent 30 years working for the United Nations, including a post as assistant secretary general for human rights.

In The Burning Question, he lays out stark facts and offers practical solutions to the issue that fundamentally threatens life on Earth. “People are now talking about the impact of climate and conflict but there was no book on it,” he reflects. “This is the first – and definitely will not be the last.”

With global greenhouse gases emissions increasing, and because of the gases already in the atmosphere, temperatures will continue to rise even once emission levels are reduced. But funding is focused on mitigation not adaptation. And as Andrew points out, funding across the board “falls far short of what is necessary to address the social, economic, humanitarian needs of adaptation, much less to address the resulting security issues simmering below the surface”.

In 2004 Andrew was based at the UN regional office for West Africa. “I realised there is a much greater link between the environment and human rights than I had previously acknowledged,” he said. “It seemed to me that the introduction of cheap solar cookers in the conflict zones of Sierra Leone, Liberia and Cote d’Ivoire would be the obvious solution to several problems.

“They would reduce the need for women to travel large distances to collect wood, with many of them where raped or abducted on their journeys. It would help with respiratory health, and would cut down families spending money on charcoal.”

No solar cooker was ever distributed – but it set Andrew to look at how the framing of climate change as a threat to peace has been slowly gaining currency.

He adds that if policy-makers recognise the dangers climate change poses to security, they would be moved to act more radically.

“The struggle for control of vital natural resources is as old as humanity itself,” he writes. “Climate change is already resulting in an increase in the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events that damage the production of crops and diminish essential clean water sources. In areas where the quality and availability of resources such as water and fertile soil determine livelihood opportunities, climate change undermines human security and fosters the socioeconomic conditions known with certainty to drive conflict.”

Climate breakdown was discussed by the UN Security Council in 2007, but caused concern that by “securitising” climate change, there could be a focus on military answers. However, it is vital agencies responsible – and with tools to help – are co-opted.

“It is surely a positive development if some of the enormous resources and political attention devoted to defence can be leveraged for climate purposes,” he says. “Militaries tend to be well-resourced, large scale and effective. They can be mobilised quickly and can provide support above and beyond their fighting capabilities.”

The impact militarisation has on our planet is stark. “The US military alone is estimated to have a greater level of emissions than most nation states,” he cites.

The book looks at how Russia’s aggression in Ukraine has created a myriad of problems, from the impact of the war directly on the environment – the blowing up of dams, flooding of land and the huge amount of fuel burned by armies – to the need for the West to find other sources of gas and oil in the face of sanctions against Russia.

“Putin’s invasion has various climate ramifications,” he says. “The price of fuel rose and it led to more productivity. It opened up questions as to where we get our fossil fuels from – for example, there were calls to open a coal mine in Cumbria to cut reliance on Russian fuel. But then people began to say – it is not sustainable to be dependent on fossil fuels – so this can be a push for action.”

More than 60 per cent of Russian territory is far north enough to be covered in a permafrost – when this melts, it will give the Russian state land to exploit for agriculture while less ice in northern seas will create new trade routes and new opportunities for exploring ways to exploit natural resources – including oil and gas.

“Russia has less to lose from climate change than any other country, and as a petro-state more to lose from a move away from fossil fuels,” says Andrew. “It is hard to avoid the conclusion that disastrous climate change is seen by at least one global player as being in its own long-term strategic interest.”

For Putin, the climate crisis presents a further opportunity – he sees migration as a tool that can destabilise Europe.

“The dominant feature of the next two decades and more is likely to be migration on a scale that has never been experienced before,” writes Andrew, citing the experience caused by the Syrian conflict: “If one million refugees could convulse the liberal political settlement in much of Europe in 2015, what would 10 million do?”

By 2070, a mean temperature of 29 degrees could cover a fifth of the planet, making vast areas uninhabitable.

He shows how the far right feeds on fears over migration and their agenda has some irony.

“Although far right parties generally express an extreme fear of immigrants… they in fact find immigration deeply advantageous politically,” he says.

Climate and conflict has become a tool in the right’s “culture wars”.

“Climate change and net zero policies are being instrumentalised as an electoral wedge issue by conservative or far right parties. George Monbiot has written: ‘The two tasks – preventing Earth system collapse and preventing the rise of the far right – are not divisible. We have no choice but to fight both forces at once.’ And there has been so much disinformation from the likes of the Murdoch media, the Telegraph group, who dispute the facts and try to frame it as Net Zero Wokery,” he says.

“Proposals for heat pumps, bicycle lanes, low traffic and reduced cattle herds are presented as mortal threats both to freedom and prosperity.”

And there is the idea of equity, he adds.

He says: “It would be quite wrong to caricature calls for climate justice as ‘radical’ or anti ‘Western’. Rather climate justice should be embraced as the means of reducing both global inequality and planetary collapse.”

Somalia, for example, is currently experiencing massive disruption due to climate change.

“They are just not responsible,” he says. “The total emissions since 1960 emitted by Somalia is equivalent to what the US emits in just two and a half days. We have a moral obligation towards people forced to leave their homes, not because of their emissions, but because of ours.”

• The Burning Question: Climate and Conflict – why does it matter? By Andrew Gilmour, The Berghof Foundation, £15