Paris protests with balaclavas and samba

Assistant editor Anna Lamche dodges tear gas in the French capital as she reports from a charged 1er Mai demonstration

Friday, 5th May 2023 — By Anna Lamche in Paris

Amid the flare smoke, a samba dancer keeps on performing

FOLLOW US ON FACEBOOK. CLICK BANNER.

By Anna Lamche in Paris

PARIS feels subdued in the lead-up to the 1er Mai demonstrations. Save for the smashed shop windows and graffiti scrawled on statues and walls, there is little evidence of the protests that have shaken the French capital in recent weeks.

The metro runs efficiently, the bin men are back at work and the shopping district is open for business as usual. Only the posters promising a “tidal wave” of protest hint at what’s to come.

The country has been wracked by a series of strikes and protests since French President Emmanuel Macron announced his pension reforms earlier this year, raising the retirement age from 62 to 64 and increasing the number of years French workers have to contribute to the system before they can withdraw their full pension.

But the protests are about more than just the pension reforms.

As Labour in Paris member Tom Owen explains, in the current French political climate “it could have been anything” that sparked the protests.

The new legislation has acted as a flashpoint in two respects, signalling to many onlookers the erosion of two fundamental rights underwritten by the French constitution: the right to democracy and the right to assembly.

Fireworks are lit, while the press photographers, below, need protective kit

Controversially, the reforms were pushed through without a vote in the French Parliament last month using a special “decree”, adding weight to long-running accusations that Mr Macron is acting more like a king than a President.

Meanwhile, protesters gathering on the streets have been met with increasingly repressive force by the French police, who arrive in riot kit, wielding truncheons and tear gas. One protester lost a thumb at a recent protest; another lost a testicle.

As Mr Owen says: “Police like to demonstrate the fact that they’re police.”

For many in France the pension reforms have become a symbol of the condition of the country, as the welfare state is eroded, democracy is undermined, and protest is met with militarised violence.

And symbols matter in France: rising gas prices were enough to bring the “gilet jaunes” (yellow jackets) out in force in 2018, igniting protests that spoke more broadly to the living conditions of the working-class population living outside the country’s urban centres.

Masked drummers and, below, people come out onto balconies with pots and pans

The Fête du Travail, held every Labour Day, is an important public holiday for the French. Every year a “manifestation” – half carnival, half demonstration – weaves its way across the capital.

This year 1er Mai is particularly charged, as millions prepare to take to the streets in protest at the reforms.

On Monday, people begin gathering in their hundreds in Place de la République from as early as 10am, preparing for the afternoon demo.

Union leaders park up their vans and set their speaker systems blaring; protesters mill around wearing gilet jaunes, eating hotdogs sold from nearby stands and handing out leaflets.

Nearby, women’s rights campaigners in blue utility jackets and red rosettes – “a symbol of women fighting during the Second World War,” according to group member Karen – fix ghoulish effigies of Mr Macron and prime minister Élisabeth Borne to their van.

Karen, who asked us to withhold her surname, tells me the reform particularly impacts women. “We used to have two years less of contributing to the pension for every kid that we had, and this is literally being cancelled,” she said.

At the same time, young members of Extinction Rebellion in climbing ropes and harnesses scale the statue at the centre of the square, unfolding an orange flag to cheers from those watching below.

Matisse Montreux

As eighteen-year-old Matisse Montreux says: “We want a republic that proposes an ecologic system and social system that doesn’t make us work too long for nothing… we are angry… I hope for a new president, a new democratic system which represents us all. “We want a sixth Republic. We don’t like the fifth.”

Overall the atmosphere is reminiscent of carnival, although men wearing balaclavas and black clothes congregate in one corner of the square, setting off fireworks against the pavement.

Alex Norman from Labour in Paris

During an interview with Labour in Paris chair Alex Norman, we are told to move on by two protesters in balaclavas. Mr Norman says the atmosphere is “tense” in certain parts of the square.

“They believe that all press, and foreign press, is in the hands of the power. So when we talk to them, we are [hated]. There is a little part of the movement who is like that,” he said.

According to Mr Norman, who is also a member of a trade union, the reforms are an “important issue for France” because “it’s like if you change the NHS system without a law in England – it’s really the backbone of the social contract.”

For another protester, Lara Bakech, Macron “does what he wants without explaining and justifying and all the justification he gave was wrong,” she said.

The French government has suggested that the pension system could be as much as €150 billion in deficit within the next decade; independent auditors put the figure closer to €10 billion.

The rain begins to pour as the demo gets under way, with firemen wielding flares at the front. I meet a woman who tells me she is training to be a war photographer; she is shocked I have not brought a gas mask and crash helmet.

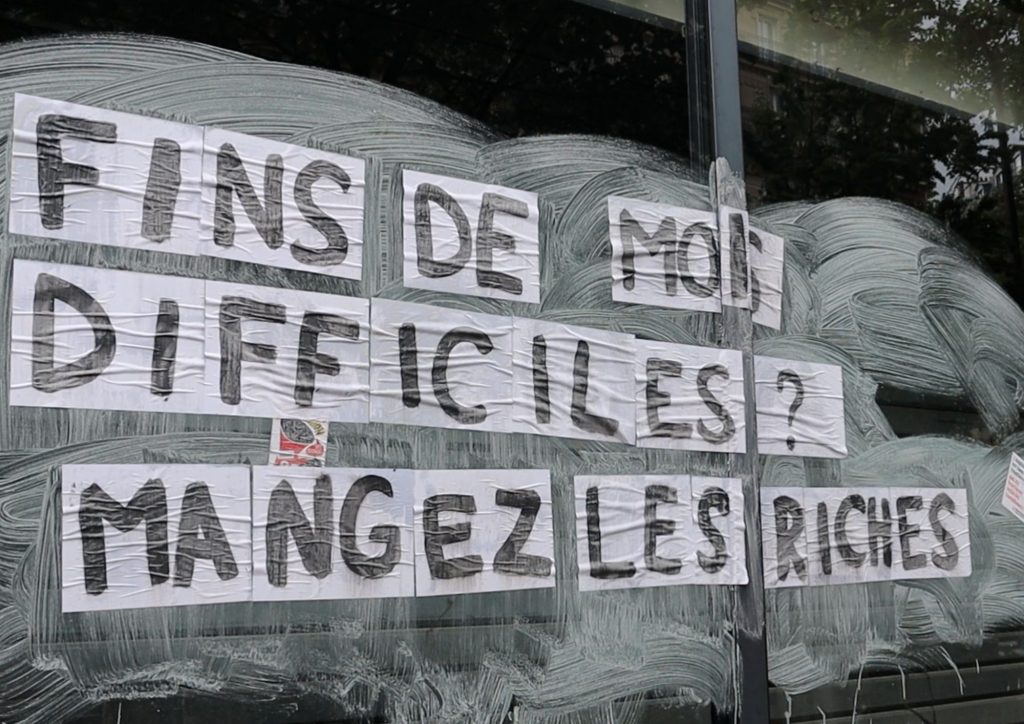

‘Eat the rich’

We see why when a minority of protesters lob Molotov cocktails and set fire to cars.

The police respond by lobbing teargas and charging at the crowd. At the Place de la Nation – a public square to the east of the city, where the protest ends, the air is thick with the gas.

Here a samba dancer in full Rio costume performs amid the flare smoke, surrounded by protesters dressed all in black jostling through the crowds.

Demonstrators scale the Marianne

Protester Karen asked us not to publish her surname, and, below, effigies of the French leadership

Along the route, police block the road, braced for trouble in helmets and gas masks, holding riot shields.

In the midst of the tension, the pessimist might argue that France offers an approximate vision of the future for many countries in the west.

For European nations strapped with ageing populations, flatlining productivity and stagnating wages, a healthy welfare state is becoming increasingly difficult to maintain – particularly when leaders are reluctant to tax extreme wealth.

Heavily featured in the school curriculum, the Revolution lives on in the collective imagination of the French and still serves as a reference point for many across the country and perhaps undergirds the determination to come back again and again to the centre of Paris.

In England, the response to the French protests has been an almost sheepish chuckle at our own pension age: currently pegged at 66, but likely to rise higher.

Of course, England has a radical history of its own – albeit one that is rarely taught in schools – stretching from the poll tax riots of 1990 to the miners’ strikes of the 1970s and, further back, to the Suffragettes, the Tolpuddle Martyrs and the Chartists. But the ruling classes here have proved remarkably adaptable, as subversive ideas are absorbed – or, to use Guy Debord’s phrase, “recuperated” – into the ruling order.

Our institutions, it might be argued, bend to pressure in order not to break. Further complicating the picture is the fact English trade unions – typically the nerve centre of serious protest – have been hobbled in a way that is inconceivable in France.

In England, protest is often quietly repressed using the law, as the legality of large “disruptive” gatherings are brought into question – the recent environmental action being a case in point.

On both sides of the Channel the implication is that instead of dealing with the root causes of decline, those in charge will opt for short-term fixes, bypassing the democratic process and using a range of measures to repress protests.

But for now in France, where some see oncoming collapse, others will see a healthy democracy at work, as citizens from across the social and political spectrum engage in political debate and come together in solidarity to defend their rights.

Amid the uncertainty, we should take courage from the French: like them, must not go down without a fight.