New Journal founder Eric still had points to make as he helped to edit his own funeral service

His advice was: be yourself, be authentic and don’t follow the mob

Thursday, 15th April 2021 — By Richard Osley

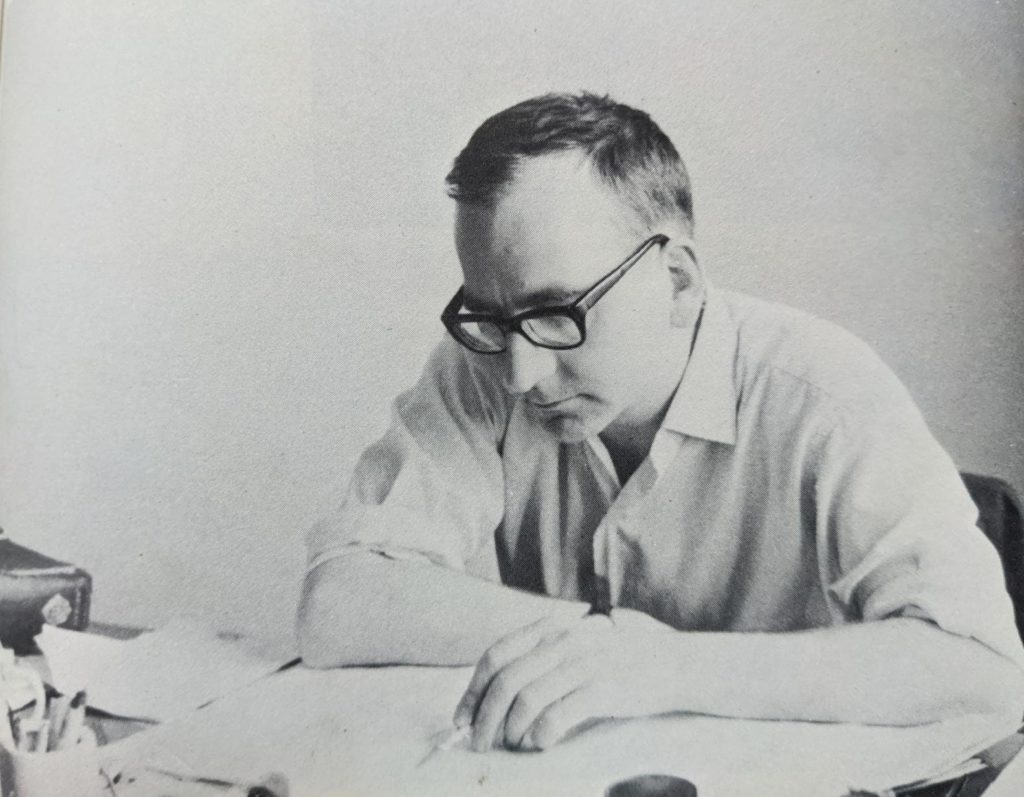

Eric Gordon in the CNJ offices two years ago

AN editor until his final moments, Eric Gordon – the founder of the Camden New Journal – helped write his own funeral eulogy.

As cards, flowers and tributes continued to flood into our offices, Eric, who died aged 89 on Easter Monday, was buried alongside relatives at the Jewish Cemetery in Brighton on Thursday afternoon.

During a socially-distanced service with close relatives and friends, his eldest son Kim – wearing a hat that could easily have come from Eric’s own collection – explained his father’s extraordinary life story.

He said that Eric had called him into hospital in the final fortnight of his life where he had asked to be interviewed about what to say.

“He was a journalist – he still wanted to make some points,” said Kim.

“So who was he? He was first of all Jewish, an individualist, a communist.

“And anybody who knows about these things, knows there’s a bit of a contradiction in any of those things – but nevertheless that is what he said at the end, and he said ‘there’s quite a few of us’.”

Eric Gordon in China in the 1960s

He added: “He was a rebel with a cause and the cause was the working classes. It didn’t quite hit me until later but he was basically a young working-class boy from north Manchester – and everything he does is about relating to those people, like him.”

Eric’s family had been financially poor, but “culturally very rich”, Kim said – the home being full of music, not least because his father Sam had ambitions to play the xylophone in music halls.In that hospital ‘interview’, Eric also said his views had been shaped by the anti-semitism he had suffered as young as eleven and that he had regularly been beaten up for being Jewish.

He had begun rabbi training at the Gateshead Yeshiva but walked out, convinced by his elder brother, Jeffrey, who had become a communist. The reading of Thomas Paine’s The Age Of Reason also proved influential.

Kim Gordon delivers his tribute at the cemetery

At 18, he had joined the Young Communist League in Manchester.

“He actually said at that time he swapped one religion for another: Judaism for Marxism,” said Kim. National service saw Eric serve in the Royal Medical Corps, where Kim said he met “middle-class people” for the first time as he served as the PA to the chief pathologist. After moving to north London, he met his first wife, Marie, at a Communist Party meeting and they travelled often to eastern Europe.

Later, they decided to move, with Kim still a boy, to China, intrigued by Maoist thinking.

“But what does he do?,” Kim told the service. “He says ‘I know better than you’ to the Chinese Communist Party, I’m going to write some books and articles about how good the Cultural Revolution is.

“Everybody said don’t start writing these notes but he did and he told his friends that he would hide them behind a picture of Chairman Mao because ‘I have to smuggle them out to help the cause’. The security police found out and they took us away. So we spent two years in hotel arrest and them trying to get him to confess to unconscious spying.”

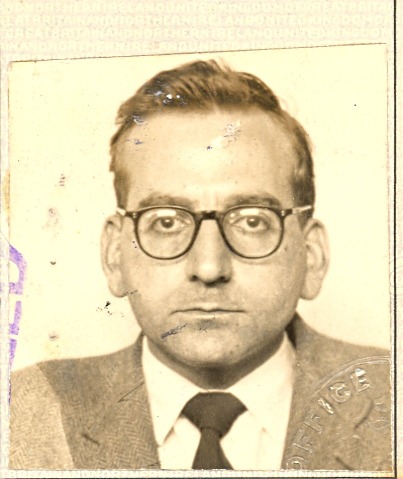

An old passport photo

He added: “Wherever he is now, maybe he is smirking about it because I suspect the interrogation became debates and sometimes the head of the security police came out looking exhausted having debated with Eric.”

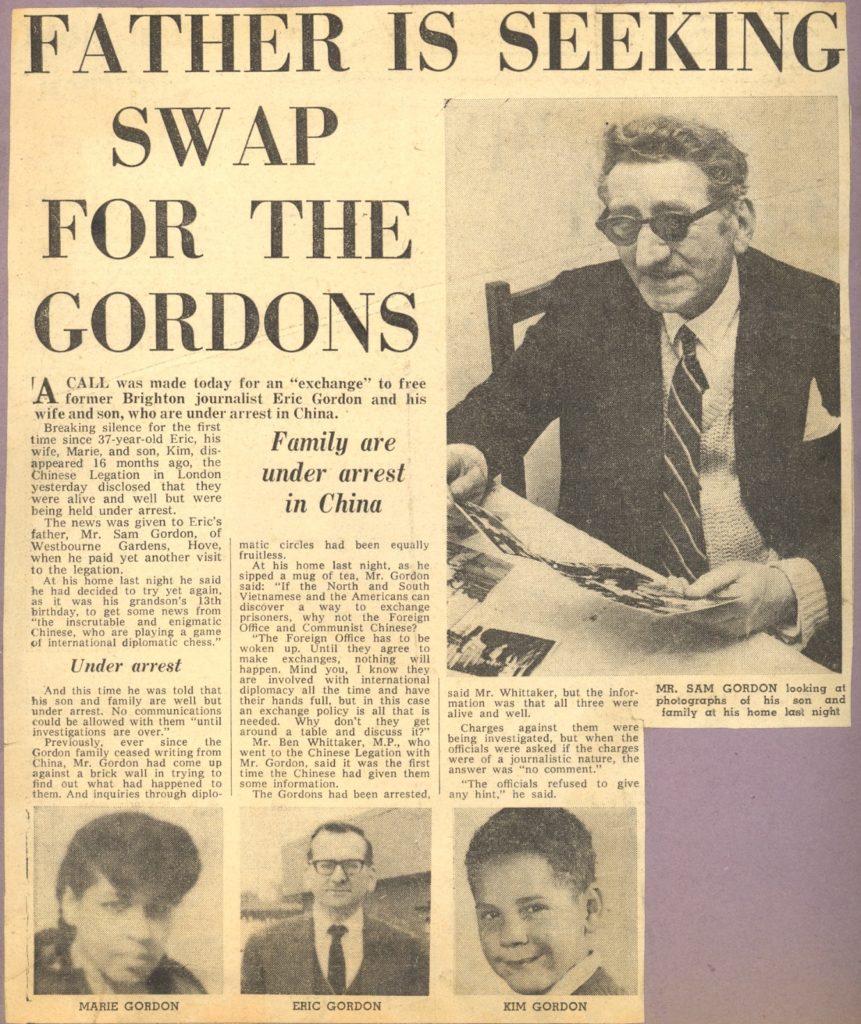

Kim has written further about their incarceration in today’s Review section. The case became an international cause celebre and later Eric wrote a book, Freedom Is A Word, about the experience.

In later life, he sometimes told colleagues that he had written it too soon after returning home and that he would have liked to write a new one.

Eric worked for a series of newspapers in Brighton – his father was living in Hove when he was making appeals for his son’s family’s release – Nottingham and Chiswick.

He worked on the Daily Metal Bulletin and the Daily Herald too, and in the 1970s he was heavily involved with the National Union of Journalists.

“Naturally, he wasn’t an ordinary journalist, he was always organising protests for the workers,” Kim said.

“In fact one of the more bizarre things when I went to see him in hospital was that he asked: Were you on the demo? He meant the ‘Kill the Bill’ demo in Brighton last week.”

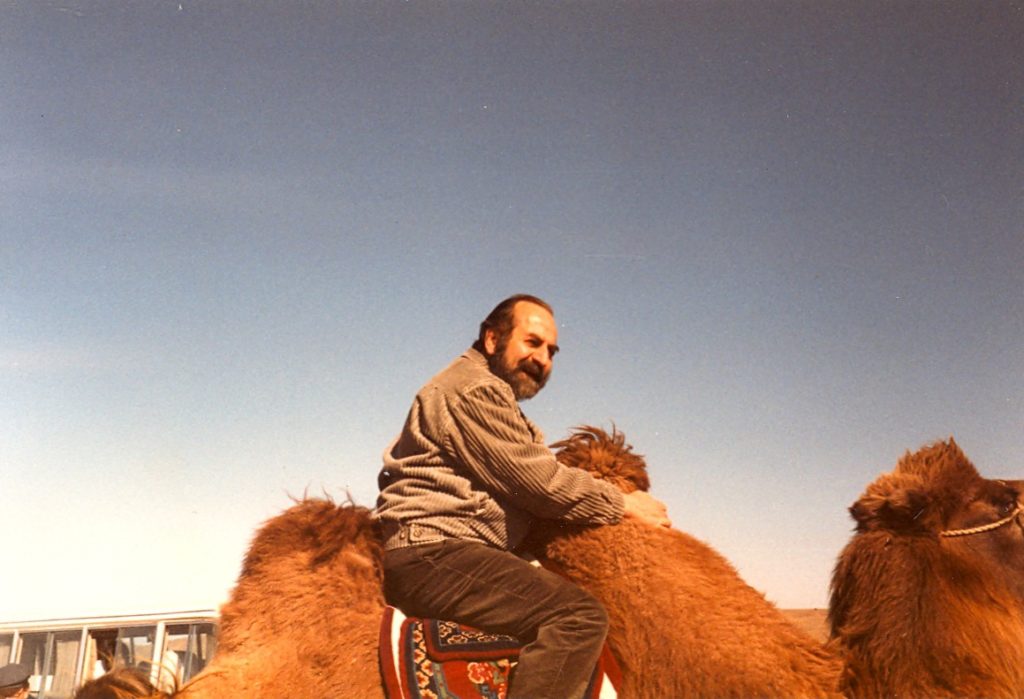

An overseas adventure

As we detailed last week, Eric was one of three original founders of the CNJ in 1982 alongside the late Frank Branston and the journalist, Angela Cobbinah.

The formation of the paper followed a 16-month strike against newspaper closure and the unceremonious sacking of reporters on the old Camden Journal.

As part of the settlement, the newspaper’s owners sold the title for £1 and the “new” paper began. “The paper is an actualisation of himself in many ways: a paper for the working classes – a people’s paper, but with a rich culture too,” said Kim.

The CNJ went on to become a campaigning voice, playing pivotal roles in he fight to stop the closure of public services and privatisation, including, at different times, hospital units at UCLH and the Whittington.

While the tenor of his views was hardly concealed in his own comment pieces, the paper had been celebrated since its beginnings as being open to all.

At the same time, he took on the role of mentor to waves of young reporters who last week were fondly recalling his tutelage.

Sister papers in Westminster and Islington followed.

His father Sam in a clipping during the campaign to secure Eric and his family’s release

More recently, Kim said his father – whose hebrew name was Ephraim – had reflected on anti-semitism and Judaism.

“He asked for a mezuzah to be placed on his door,” said Kim.

“He said this was not just for religious reasons but because he wanted to tell the world that a Jew lives here – I am not afraid.

“It reminded me of the only time I had seen him physical and it was in Hampstead High Street when I was 13 or 14. He saw some National Fronters giving out leaflets and he took them, tore them up and threw them to the ground.

“I was agog but he was basically saying you beat me when I was young but I am getting you back now – and he did.”

Kim added: “His advice was: be yourself, be authentic and don’t follow the mob. When you think about him, it was simple really: unwavering faith, extraordinary effort and use any skills you have on behalf of the working people of the world.”

A copy of the CNJ was placed in the grave as he was buried. Eric died after medical complications following a fall at his flat in Primrose Hill.

He is survived by his wife, Samantha, who writes a personal tribute to her husband in today’s paper; his sons Kim and Leigh; and Elly, his daughter with former partner Angela Cobbinah. He had five grandchildren and one great granddaughter.