Moving pictures: how travel has influenced artists

Social historian Travis Elborough has chosen 31 journeys taken by prominent artists – and considered how they have shaped their work

Friday, 20th June 2025 — By Dan Carrier

Travis Elborough, author of Artists’ Journeys that Shaped Our World

IT was hardly the most romantic of surroundings – but for the artist Oskar Kokoschka and his bride Olda Palkovska, the bomb shelter at Hampstead Town Hall was at least safe from German bombers hitting the capital.

The date was May 15 1941, and while the happy couple might have imagined a different setting, Hampstead had offered them a safe haven as they built a life together.

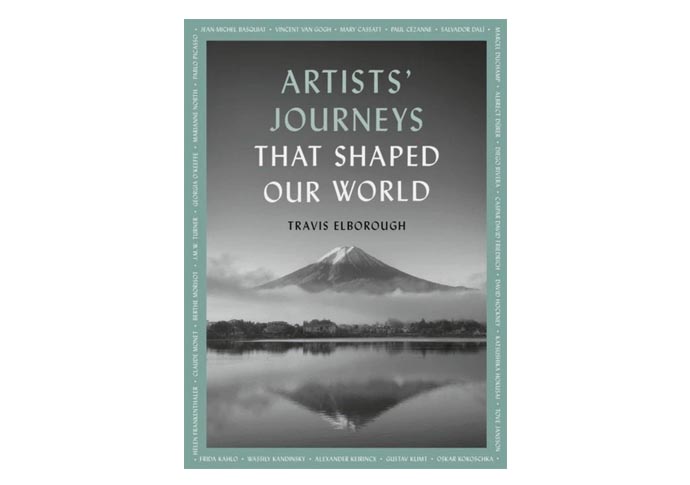

Kokoschka’s journey from the town of Pochlarn in the former Austro-Hungary empire to Haverstock Hill was via Vienna and then Prague – and his journey is subject of an essay in a new book, Artists’ Journeys that Shaped Our World, by Highgate-based author Travis Elborough.

In it, Travis has chosen 31 journeys taken by prominent artists – and considered how their travels have influenced their work.

Alongside Kokoschka, he looks at Claude Monet’s journey to Victorian London, Salvador Dali’s voyage to New York, Pablo Picasso’s to the south of France, Henri Mattise in Morocco and Paul Klee in Tunisia.

“Klee once suggested that drawing was simply taking a line for a walk,” says Travis. “A walk, however, can only take you so far. In the interests of expanding his own horizons, Klee embarked on a Bildungsreise – a voyage of personal growth and discovery – that lead through to a breakthrough in art.”

Klee travelled to Tunisia and was profoundly moved by what he saw: “Klee’s trip is a prime example of the king plotted in this atlas,” adds Travis. “For some, like Klee, travel was a turning point.”

For Kokoschka, travel was enforced – but would help him build up a vision of his work. The artist had left Vienna in 1934, worried by the rise of Nazism – “his art was denounced as degenerate,” adds Travis.

He became a Czech citizen but his time in Prague was to be cut short when Hitler sent troops into the Sudetenland and Neville Chamberlain secured the Munich agreement. “Oskar and Olda fled Prague, flying to London via Rotterdam, carrying the unfinished painting Zrani on the plane with him.”

They found a haven in Belsize Park, settling in Belsize Avenue before being helped by supporters to find a more permanent place in King Henry’s Road. Directors of the Tate and the National Gallery found him work teaching and commissions.

Hampstead was becoming a vital meeting place for refugees – and Kokoschka met the Artists Refugee Committee, based in Downshire Hill and worked with others to warn of the threat Nazism posed. “During his time in London, he painted Prague, Nostalgia – a melancholy picture evoking his final impressions of the Czech capital.”

But by the summer of 1939, London’s expense and the need to find somewhere that would allow him to paint in quiet surroundings saw them head for the small Cornish port of Polperro.

“He called his new home ‘a beautiful, healthy place… much lovelier than a cosy Italian port because [it is] so much more real’” explains Travis.

By 1940, as invasion threats saw stricter rules about where people could settle, Kokoschka and Olda were forced back to London, and Hampstead’s makeshift register office.

As well as more contemporary travels such as Kokoschka’s, Travis goes back to the Renaissance, describing how Caravaggio fled Rome in 1606 following the killing of Ranuccio Tomassoni after a row with the famously hot-headed artist turned violent.

He describes how Claude Monet left France for London during the Franco-Prussian war and found a lively Anglo-French community thriving in Soho, and the impact the west coast of America had on David Hockney.

“Travel, until comparatively recently, could be arduous and dangerous,” adds the author. In centuries gone by the arts might be leading to lands that were only sketchily mapped out and that few others concerned themselves with, their subsequent depictions of such out-of-the-way territories and strange wildlife possibly just as thrilling in their day as the first satellite images beamed in from the moon in more recent times,” he adds. “During periods when a whole continent might be plunged into conflict, an oddly dressed foreigner who stopped to sketch a local landmark might be viewed with suspicion of outright hostility.

“Conversely, the detention arrived at could be a place of comfort, safety or refuge and the balm offered a necessary condition to continuing to paint or draw.”

As Travis’s beautifully illustrated and thought-provoking commentary reveals, artists are moved by what they see – and gazing with fresh eyes on ancient views can inspire new ways of expression.

• Artists’ Journeys that Shaped Our World. By Travis Elborough, White Lion Publishing, £14.99