Miller’s tale

In an unusual addition to his series on eminent Camden Victorians, Neil Titley considers the colourful life of American poet and frontiersman Joaquin Miller

Thursday, 29th December 2022 — By Neil Titley

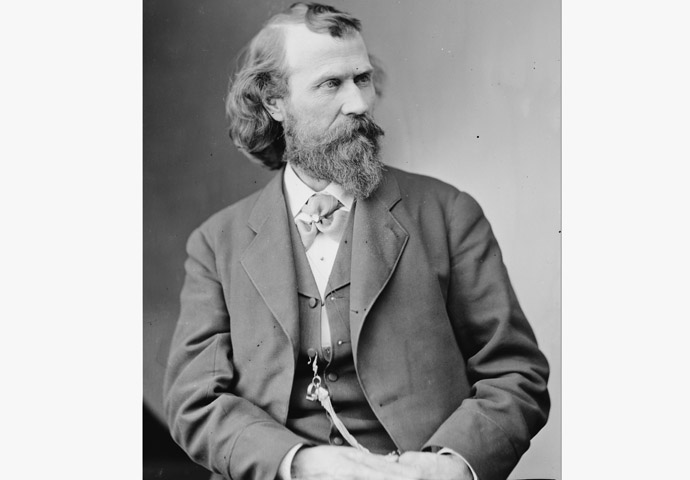

Joaquin Miller, 1837-1913

MANY itinerant North Americans have temporarily alighted in Camden. In Hampstead alone one remembers Tony Curtis displaying his paintings at the Catto Gallery, David Soul plotting politics in La Gaffe restaurant, and Leonard Cohen drinking in the King William IV. But very few of them have been as colourful as the poet Joaquin Miller (1837-1913).

Miller constructed his entire career on his experience of the American frontier. Although born in Indiana, his family set out by covered wagon on the Oregon Trail in 1852. They were attacked by Sioux and were fortunate to survive. Miller’s father, a resolute Quaker, refused to fight, while Joaquin himself was armed only with an old flintlock rifle that in the heat of battle he discovered to have no flint. Fortunately other members of the wagon train drove off the assailants.

After his family had settled in Oregon, in 1856 Miller set off for the Californian goldfields. While there, he fought in several minor skirmishes against the Modoc people and, after he had been cheated of his wages, stole a horse from his employer and fled to the mountains.

This was a serious offence. Miller was captured and imprisoned in a county jail. With the aid of a fellow prisoner named Jack Marshall, he escaped by sawing through the bars of his cell and headed once more to the mountains where he stayed with Marshall and his gang of desperadoes.

Mistakenly thinking that the fuss had died down, he returned to drink in a saloon, was quickly recognised, and had to back out of the bar while covering the clientele with a revolver. After a gunfight with a pursuing posse, Miller made it back into the woods.

For a while he avoided civilisation and followed the native American lifestyle, living by hunting and fishing, and setting up home with a woman who bore him a daughter named Cali-Shasta. Later, he moved on and became a cook at a mining encampment where he became known as “Crazy Miller”. After becoming sick with scurvy as a result of his own cooking, he returned to Oregon.

His next venture was to become a partner in a pony express company. This was dangerous work, often beset by the ferocious Chinook winds of the Rockies and with the constant danger of attack by “road agents” (highwaymen).

On one occasion, he was carrying gold dust down a mountain when his horse shied, then plunged off the track and down the hillside. A moment later a hail of bullets swept over the area they had just left. The horse carried him to safety from the road agents before it collapsed and died from gunshot wounds.

By 1860, Miller was studying law while also editing a small newspaper. In 1866 he was appointed as a judge. Dissatisfied with Oregon, he returned to California determined to break into the newly emerging literary circle of San Francisco. When his overtures were rejected he decided to try his luck in England and in 1870 moved into lodgings at 11 Museum Street in Bloomsbury.

Initially, he had no more luck than in San Francisco. Then he changed tack and decided correctly that if he wore the flamboyant costume of the Wild West, automatically he would stand out as a sensation amid the sober attire of Victorian England. Hence he was never seen without a buckskin jacket, a scarlet sash, a large knife in his belt, and with his hair flowing to his shoulders. Touting himself as “the Byron of Oregon”, he published his poems at his own expense and they became popular.

However, when Mark Twain arrived in London, he found Miller’s caricature of an American intensely embarrassing. At one society dinner, he cringed when Miller lifted up a large fish from a tureen and swallowed it whole. Miller brushed off Twain’s distaste with: “It helps sell the poems! And it tickles the duchesses.”

Joaquin Miller in later years

Miller returned to the States as a relatively rich man and determined to continue his career as a stage American even on home territory. To this end he constructed a log cabin in Rock Creek Park, Washington, DC, and adorned the walls with wild animal skins, bows and arrows, etc.

In his old age, Miller still indulged his taste for adventure. In 1897 he travelled to the Klondike gold rush in Alaska, where he endured a frightful 300-mile journey through blizzards, the disappearance of all his food, and the loss of two toes to frostbite to arrive back in Dawson City more dead than alive. Miller: “I would not be tied up in this lorn, large, desolate, largeness another winter for all the Klondike gold.”

He spent his last years back in California. There he was able to indulge his love of hard liquor.

• Adapted from Neil Titley’s book The Oscar Wilde World of Gossip. See www.wildetheatre.co.uk