Lost Warriors: Seagrim and Pagani of Burma

Although remembered as ‘chalk and cheese’, two British soldiers became unlikely comrades in arms amid the horrors of the Far East in 'the last great untold story of WWII'

Thursday, 18th September 2025 — By Dan Carrier

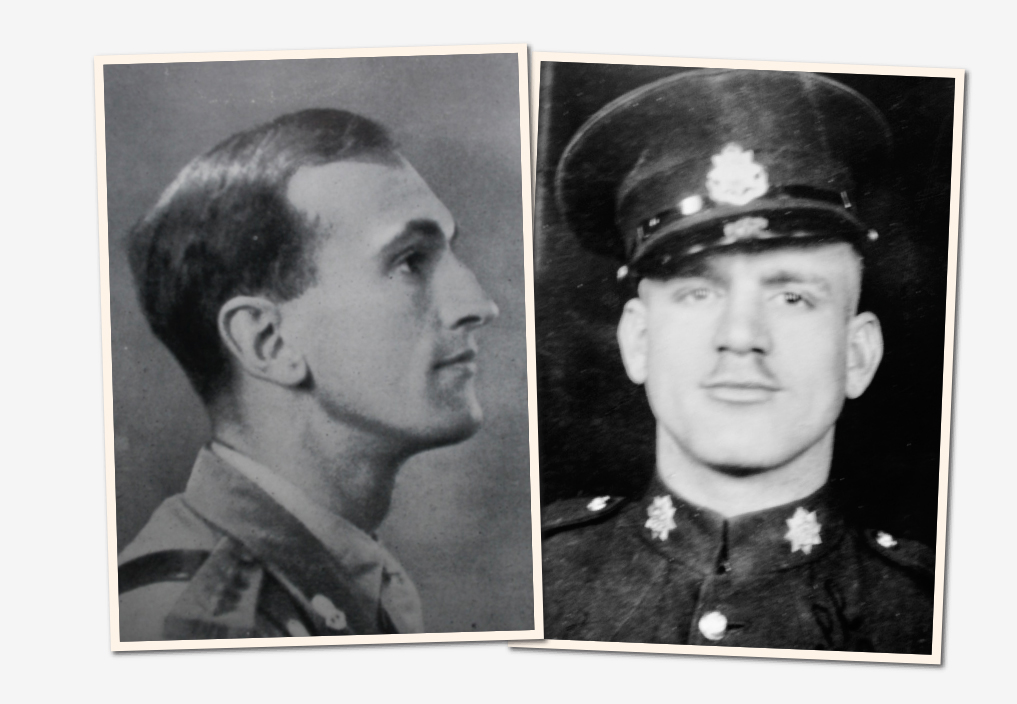

Hugh Seagrim and Roy Pagani

VICIOUS fighting in horrendous conditions, facing an enemy that gave no quarter and who treated captives with unimaginable cruelty – the Second World War in the Far East devastated millions of lives.

Within the maelstrom of conflict, individual stories of sacrifice and resilience cast light on the war’s impact – and now a new book by Hampstead-based historian Philip Davies tells for the first time of the extraordinary experiences of two British soldiers who fought behind Japanese lines in Burma.

Major Hugh Seagrim, who would be awarded the George Cross, volunteered to stay behind when Japan overran Burma between 1941 and 1942: he took to the hills where for two-and-a-half years he organised a fighting force made up of the Karen people.

Alongside Seagrim’s story, Philip tells the plight of Roy “Ras” Pagani, a serial escaper who, on his own, got clear from advancing German troops at Dunkirk and did the same as Singapore fell to the Japanese.

Pagani would later be caught and forced to work with other prisoners of war building the infamous death railway across Burma – and would be the only British soldier to escape from there. He would join with Seagrim and under his direction he would take up arms in a guerilla war.

“Dismissed as an eccentric, if charming, crank, Seagrim was destined to become one of the most characteristic guerilla leaders of the entire Second World War,” says Philip.

Philip is the former director of English Heritage and his work has taken him to India and Burma to research historic buildings and work in conservation.

It was during a trip to Burma in 2002 that he came across a tantalising sentence in a book on the country. “There was one line about Seagrim,” he tells Review. “I had not heard of him, nor that someone had stayed behind.”

He discovered a 1947 book by Times correspondent Ian Morrison called Grandfather Longlegs – Seagrim’s nickname among the Karens. “In an appendix, there is a short memoir by Roy Pagani,” he says.

Philip traced both the Seagrim and Pagani families and has brought their stories together.

Seagrim was Sandhurst-trained and in 1931 was posted to the 1st/20th Burma Rifles. He loved Burma: “Seagrim was dazzled by the beauty of the country and its engaging people,” writes Philip.

He developed a deep bond with the Karens, an ethnic group based in a hilly, jungle region.

Philip quotes Neville Hogan, an ex-Chindit who was half-Irish and half-Karen, who described Seagrim as “tall, clean-looking, he spoke the language of the Karens. He loved the people and was a brilliant officer.”

Philip adds: “Seagrim cared little for the brittle racial and class nuances that were the hallmark of pre-war colonial life. An accomplished rider, he eschewed polo, disdained the snooty horsey set and referred to the cavalry as ‘horse wallopers.’

“He was his own person, a lateral thinker, athletic, but quiet and introspective; cranky, perhaps. He made a great impression on all who met him.”

Roy Pagani was a corporal in the Reconnaissance Regiment – “a combative, barrel-chested squaddie with the heart of a lion,” says Philip.

Born in Fulham in 1915, he grew up in a French convent after being abandoned by his English father, who had kidnapped him from his French mother.

He would learn survival skills as a teenager – everything from mending shoes and knitting to cooking, hunting, farming and foraging.

He enlisted in the early 1930s and in 1939, after service in India, he met his future wife, Pip. They married a week before war broke out. It was a promise to Pip that he would return to her that kept him going during awful war-time experiences.

Pagani’s escape from the German Blitzkrieg is enough of a tale on its own. Employed as a driver for brigade headquarters in northern France, he had been told to abandon his vehicle and get to Dunkirk.

He booby-trapped his lorry by attaching a hand grenade to the fuel cap and instead of following orders, made his own way home.

“He could see incessant bombing so he turned eastwards, alone, looking for a boat,” writes Philip. “It was a perilous undertaking. Eventually he found one and sailed to England single-handedly. Four days later he reached the east coast village of Shingle Street, and walked to the door of his mother-in-law’s house, who promptly fainted.”

Pagani’s 18th division was then sent east – and his Dunkirk trial was to be a prelude to similarly testing experience.

He was captured after the fall of Singapore and as a Prisoner of War was put to work by the Japanese building the infamous Burma railway. He escaped by heading into the jungle with the aim of walking across Burma and into India and safety.

En route he heard of Seagrim and was taken to meet him. He would help Seagrim organise resistance before once again having to try to escape from enemy territory. He nearly made it – he was caught by pro-Japanese Burmese troops with freedom in sight and nearly hacked to death as he tried to cross the Irrawaddy river.

A regular visitor to Burma for conservation work, Philip followed Pagani’s escape route. His research saw him go inside the infamous prison both Seagrim and Pagani would later be held in Rangoon.

“I bribed a guard and they let me in,” he recalls. “I saw the cells, which were just as they were in 1944. “It was a pretty haunting experience – a grim place by anyone’s standards.”

Seagrim and Pagani were thrown together through conflict. “They were very different people – chalk and cheese,” says Philip.

Seagrim was a 6ft 4ins officer, while Pagani was short, stocky and pugnacious.

“But they were both extremely self-reliant and had been brought up to look after themselves,” adds Philip. “They got on like a house on fire.

“Seagrim was unconventional – an intensely spiritual man, many said he was a missionary masquerading as a soldier.

“He was unlike the usual British Army officer. He worked alongside the Karens in the fields. He cared deeply for their future.

“He kept an anthology of spiritual quotations and poems and it gives an amazing insight into his psyche. He believed in sacrifice for others. He was a high-minded individual and not just immersed in a Christian tradition. He was interested in Buddhism and spent two months at a monastery meditating.”

Pagani also had great inner strength. After working in horrific conditions under the eye of Japanese soldiers, he took his fate into his own hands.

“Pagani made an extraordinary decision to go off into the jungle,” adds Philip.

“It was very matter of fact. He said to his comrades: ‘So long then, I am off.’ He tried to walk barefoot to India and he nearly made it.

“He tried to pass off as an Indian labourer but he was ginger-haired and had a huge tattoo on his back. He must’ve stuck out like a sore thumb.” Philip traced where Pagani had settled after the war. The soldier had set up a Clacton taxi firm and was given Ras’s unpublished memoir by his family.

“This is an epic of two forgotten Englishmen who deserve to be remembered as among the most courageous and resourceful heroes of the most savage conflict in human history,” he states.

• Lost Warriors: Seagrim and Pagani of Burma – The last great untold story of WWII. By Philip Davies, Atlantic Publishing, £20