John Gulliver: The secret life of the ‘tart carders'

New book features collection of ads found in phone boxes

Monday, 9th June 2025 — By John Gulliver

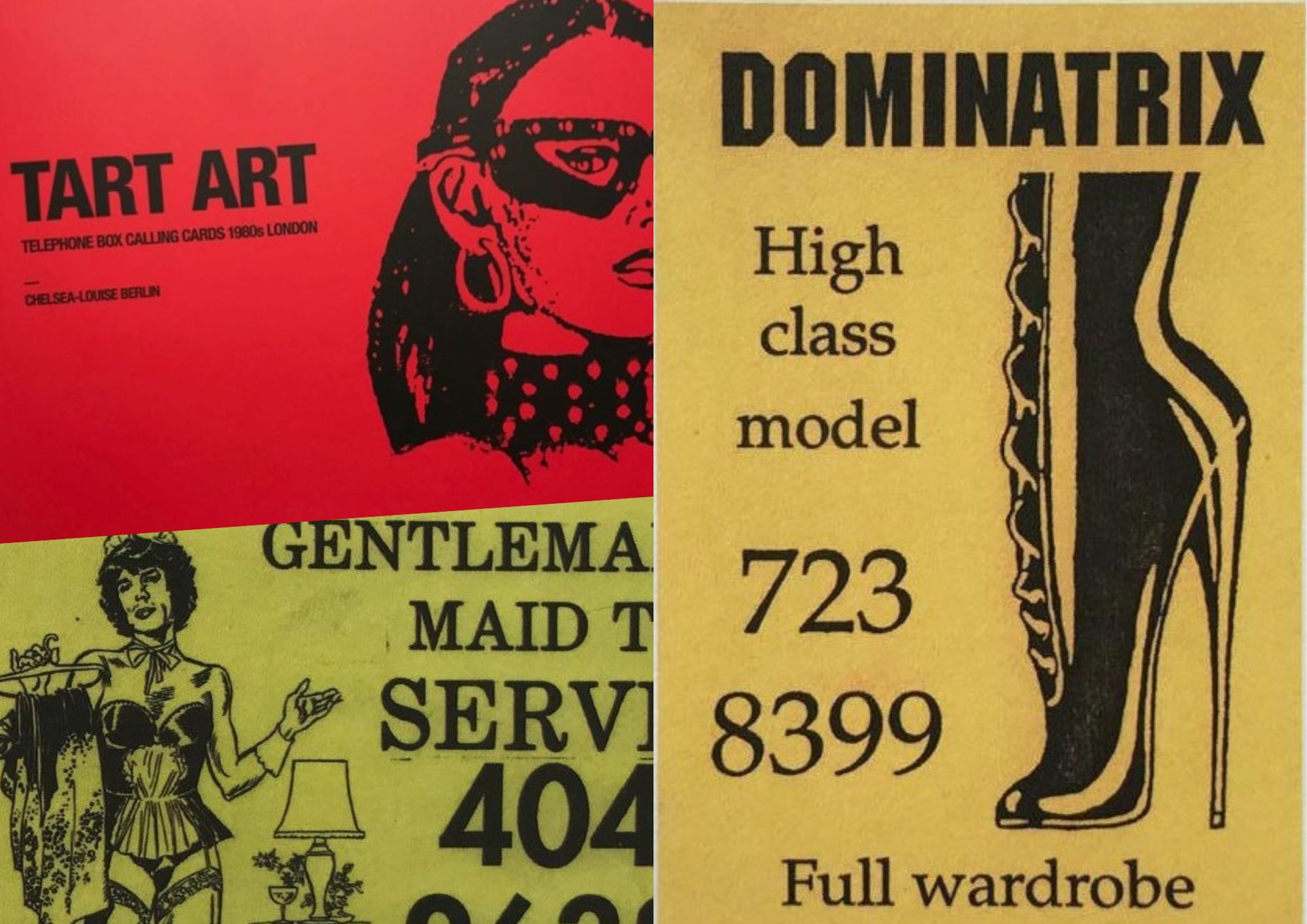

Some of the collection in a new book on adult telephone box ads

THEY are almost as famous as the iconic red telephone boxes themselves, but just how did all those “tart cards” get into the kiosks in the first place? The other day I met a man in a pub, let’s call him RD, who could answer from experience.

In the early 1990s he ran a group of “carders” paid for by various “maids” in brothels to ensure phone boxes around NW6 and beyond were fully stocked.

The job involved a relentless cat-and-mouse game as cleaners at British Telecom, rival gangs, and public “do-gooders” would remove them almost as quickly as his team could put them in.

RD saw himself as something of an innovator on the scene after playing a pivotal role in shifting the cards’ design away from the handwritten and drawn, to ones more professionally-printed with photographic images and an eye-catching design.

“Growing up on my estate in Kilburn was insane,” he told me.

“The things that were going on and what you could get into, well, let’s say that from quite a young age you had to draw a line with things you wouldn’t do and would. When I got offered this I was like ‘hmm it’s kind of on the border’ – but in the end I went for it.

“When I first started the maids would get packets of cards from WHSmith, writing the numbers on them by hand. I told them ‘this is a nonsense’. This is how my brain works, I thought: I can solve this.

“I’d find my own images, classy ones, but not perverted stuff. I found a printer in Kilburn and said I’d need thousands, but it ended up being hundreds of thousands.

“We had all the estates and most of the flats around West Hampstead, Kilburn, Maida Vale and St John’s Wood. Everywhere you went my cards were plastered all over every phone box.

“Sometimes we had to refill three or four times a day. We started following the cleaners’ vans. They’d drive up and take the cards, and then we’d go and put a fresh batch straight in. At the peak, we was earning thousands every week. But then it got quite violent. Other people tried to move in on it and it ended up in proper wars.

“Then one day I’d gone in to this flat to get the money, and the maid was so happy. She was saying how well they’d done that day because of the cards, how they had 40-50 clients. There was something in that moment… I just thought ‘hang on a minute, this doesn’t feel right’. It was lucrative thing I had going on, but in the end I had to pack it in.”

Chelsea-Louise Berlin

From pub yarns of yesteryear to the football pitches of north London, where Chelsea-Louise Berlin is still banging-in the goals.

Back in the 1980s, a decade before the RD era, Chelsea, who lives in West Hampstead, would go out picking up the cards from the phone boxes because of their artistic quality – often risking a confrontation from the carders in hot pursuit.

An accomplished designer and artist who studied at the Chelsea School of Art, she has published a gem of a book about her collection.

Tart Art is not about “the practice of the street, the advertising tricks of the curb, or sex work”, she writes in the introduction. It is about “the paper ephemera and micro-economies of visual language, coded signs, and public performance”.

The handwritten cards Chelsea collected in the 1980s never mentioned sex, she writes.

“Madams and Dominatrix used gothic text with stern words and plenty of overt orders” while “working girls would use witty and cheeky inuendo”.

But there were others, like “Sweet Charlotte”, who preferred a design showing “sex needn’t be crass and less was definitely more”.

Letraset typeface lettering and numbers would often be used, or full words cut out of books and newspaper headlines and then photocopied using Xerox machines.

Back then, they would be cut up on a guillotine and “handed to the carders to go about their positioning”.

Chelsea reflects “tart art” was one of the first advertising methods to provide an “instant link between service provider and client” – ie the card with a pay phone to make the call right next to it.

She recalls how the carders were almost exclusively “young men who follow a predetermined and regular route among the local area phone boxes, often following the cleaners, therefore keeping a constant display,” adding: “Some Madams and Dominatrix would use their slaves to carry out the carding, saving costs as well.”

She adds: “I have had some unnerving situations with those placing the cards in phone boxes. The young men want to ensure the girls they represent have the best opportunity. As such they weren’t at all impressed … not the best situation to find oneself in.”

The Criminal Justice and Police Act 2001 made placing the cards in the phone booths illegal.

But, despite this, carding does continue today writes Chelsea.

“Love them or loathe them, they’re here to stay.”

You can order the book and others by her website: https://www.chelseaberlin.co.uk/