John Gulliver: Jury majority verdicts' racist history exposed

Miscarriage of justice victims back campaign charity Appeal calls for change

Friday, 17th May 2024 — By John Gulliver

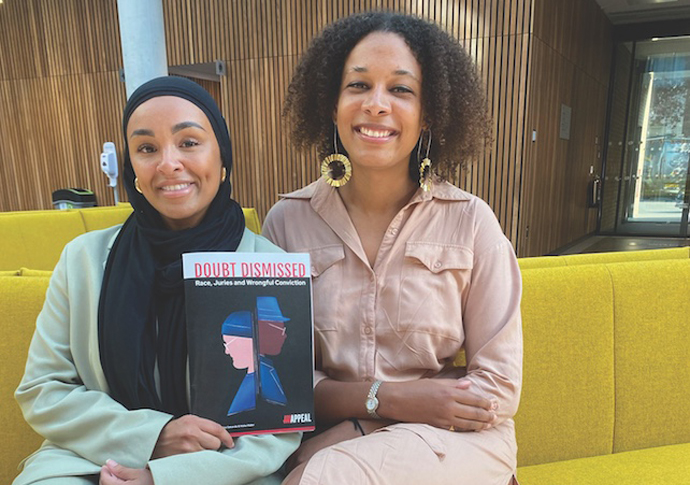

Report authors Nisha Waller and Naima Sakande of Appeal [Callaway Hoven]

There are hundreds of criminal court cases each year where a judge allows a jury to reach a final verdict without all 12 jurors being in agreement

Few will be aware of the racist and classist reasons why these so-called “majority verdicts” were introduced, as opposed to “jury unanimity”, by the Criminal Justice Act 1967.

But a report by the campaign charity Appeal reveals a direct link between public and government anxiety over immigration and the decision to scrap this centuries-old pillar of the criminal justice system.

The campaign group Appeal says this decision has tipped the legal balance in the favour of the prosecution case, leading to miscarriages of justice, and is calling for “jury unanimity” to be reinstated.

A report it launched at City University in Angel on Thursday said: “Much of the written evidence highlighted concerns that an expanded juror pool, which included the ‘labouring classes’, immigrants and ‘coloureds’, would taint the ‘calibre’ of decision- making and educational aptitude necessary for jury duty.”

Making a link with similar legislative changes in the US, it added: “Majority verdicts, which disenfranchised up to two members of a jury, were introduced in both Louisiana and England and Wales during periods of racial tension and economic instability, coinciding with fears of Black Power and white disenfranchisement.

“These changes occurred when black people were viewed as inferior yet crucial for labour, and when silencing minority voices was deemed necessary to maintain white power.”

The government of the time said the changes were about saving costs, but documents uncovered by Nisha Waller and Naima Sakande at Appeal makes compelling evidence to the contrary.

The report shows how each year more than 1,100 Crown Court convictions, around 15 per cent, are majority jury verdicts.

Some of the most high- profile miscarriage of justice cases of recent years were decided in this way, including Appeal’s client Andrew Malkinson who was recently exonerated after spending 17 years in prison for a rape he did not commit.

When asked what a judge’s majority direction to the jury meant in his case, he says in the Appeal report: “In a way, the very act of a judge going ‘I’ll accept a majority’ I think is saying to the jury have another go, you’re not reaching the right decision, have another go, which is sort of implicitly saying this guy’s guilty, we want you to find him guilty.”

Mr Malkinson with Appeal’s james Burley [Appeal]

The stories of Winston Trew – “fitted up” by a racist police officer in 1972 – Dr David Sellu – wrongfully convicted of gross negligence manslaughter in 2013 on a 10/2 majority – and Kevin Lane, convicted of murder in 1996 on a 10/2 majority – inform the in- depth report.

Ms Waller and Ms Sakande’s report concludes: “The principle of trial by jury is an essential safeguard against injustice which needs to be fortified when vulnerabilities or weaknesses become apparent.

“We have illustrated reasonable concerns that majority verdicts are likely to lead to miscarriages of justice and were introduced for no good reason.

“For this reason, we recommend the reinstatement of the principle of jury unanimity for criminal convictions in England and Wales.”