Homeland Insecurity – Professor Conor Gearty shines a light on the paradoxes of anti-terror laws

Thursday, 20th June 2024 — By Dan Carrier

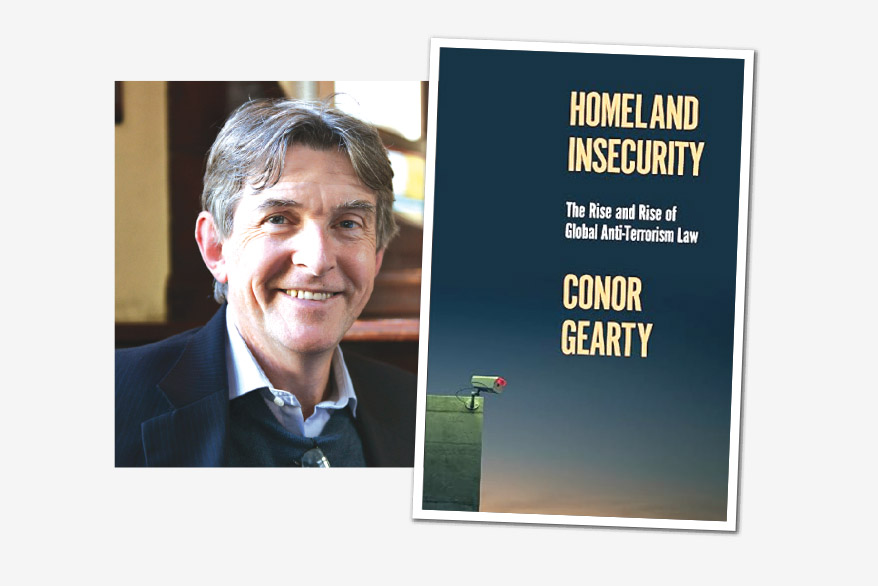

Professor Conor Gearty explores the evolution of state sanctions over ‘terrorists’ in his new book ‘Homeland Insecurity: The Rise and Rise of Global Anti-Terrorism Law’

THE war on terror has required liberal democracies to look at the values they supposedly hold dear and then turn a blind eye when their government brings in another repressive law with the excuse it is to keep you safe.

In Homeland Insecurity Conor Gearty, who lives in Kentish Town, takes the reader on an eye-opening journey through the evolution of oppressive state sanctions that aim to deal with “terrorists” – and asks what effects such laws have on society.

Originally from Dublin, Gearty is professor of human rights law at the London School of Economics. His latest book is a carefully crafted and readable walk through the history and paradoxes of anti-terror laws, and how democratic societies with a tradition of the rule of law can break out of a civil framework to use oppressive means.

While the story of state oppression goes back as far as monarchies and warlords, Gearty begins in earnest by studying the way colonial powers maintained control over subjected populations, framing it in legalese to make their repression legitimate.

“The routine acceptance of anti-terrorism laws is rooted in colonial power’s reaction to challenges to its authority, and in particular in how that reaction – often extremely violent though it was – was able to be plausibly packaged by colonial power’s domestic audiences as not inconsistent with (indeed as supported by) liberal values,” he writes.

It laid the ground for our modern terror laws.

“Colonial violence has prepared us for the excesses of the ‘war on terror’, inured us to what our supposed values surely demand would be unthinkable,” he adds.

There is a direct line from the way British governments used legal tools to commit genocide in Kenya, murder and oppress the Irish, and keep millions of Indians under the thumb.

For example, the British in India developed a strong judiciary but equally insisted certain “Acts of State” would be beyond judicial inquiry, he says.

After the First World War there was a move towards a more nuanced, law-based approach to justify crackdowns.

“We find the language of terrorism and terrorists beginning to creep into the codes and practices of counter-insurgency,” he says. “It replaced the discretion of the commanding officer on the spot with frameworks of legally sanctioned authoritarianism.”

As with the anarchist scares of the late 19th and early 20th century – which the British state had originally seen as legitimate refugees, fleeing from oppressive European governments – there was much talk of the Enemy Within. That has continued today.

He highlights how anti-terror law zones in on “a post-colonial nation having a ‘suspect community’ – ‘citizens perhaps, residents almost certainly, but not really, truly at home, not proper members of our ‘home’. The subject of anti-terrorist laws are always different because they are not truly us. This racist impulse is the beating heart of our story.”

When Britain invaded other nations and tied them to the Empire, it was natural there would be dissent and that the dissent should meet violence with violence.

“Intelligent reactions by vulnerable peoples to colonial violence have a long history: hence the need for imperial powers to come down hard on asymmetrical challenges to its monopoly of violence,” he states.

And as the 20th century grew and colonial grips weakened, new laws were introduced to firm up power.

Freedom movements, particularly in Ireland and India, condoned the use of violence for political ends and from these the modern genealogy of terrorism can be traced.

In India particularly the word terrorism was useful to “justify the creeping expansion of executive rule into the legal area”.

Ireland offers an interesting case study. Gearty points out that by the 12th century England was trying to control Ireland using both aggression and installing a political class with the tools of governance they required. In the 20th century, the Troubles saw new laws.

“Encouraged by their local Unionist master and drawing on their responses to rebellion in Palestine, Malaya, Kenya and Cyprus, the army leadership viewed the problems they encountered through the lens of their recent colonial experiences,” he says. “Curfews were imposed, suspects arrested and held on a near-arbitrary basis and multiple house searches on nationalists areas became routine. An executive power of indefinite detention – internment – was exercised in the summer of 1971. “Hundreds of supposed terrorists (all Catholic nationalists) were rounded up.”

Gearty talks of four main staging posts. Liberal democracies which had illiberal empires using the word terrorist to define anti-colonial opponents, and then the Cold War embraced this “hypocritical legacy,” while in the 1970s Israel “persuaded the world that the Palestinian question was one of global terrorism rather than national liberation.”

His final staging post is the years up to 2001.

“Islam has become the focus of terrorist-related anxiety,” he writes. “It combined all aspects of the three earlier stages – anti-imperial (seeking to challenge Western powers in its continued control of post-colonial states, such as Iran in 1979), it was Cold War like in generating fear of ‘the Muslims’ lurking as domestic enemies, and profoundly anti-Israel.”

He asks the fundamental question: “Why have double standards become so easy to maintain? How have they become embedded in the way they have?”

Gearty has laid out the circular effect of a liberal democracy using questionable means to enforce questionable laws. It reveals a history that shows the lengths states will go to to protect what they deem their interests – even if it goes against the values they say they support.

• Homeland Insecurity: The Rise and Rise of Global Anti-Terrorism Law. By Conor Gearty, Polity, £25