Interview: The Artist’s Journey: The Travels that Inspired the Artistic Greats, by Travis Elborough

‘Painters tend to be peripatetic types.’ So says social historian Travis Elborough, whose latest book examines The Artist’s Journey. Dan Carrier talked to him...

Thursday, 2nd November 2023 — By Dan Carrier

Caravaggio’s Malta [Micaela Parente-Unsplash]

IT was said the Italian master Caravaggio had taken umbrage over a bet regarding a tennis match. Unable to control his temper, he drew his sword and ran it through Ranuccio Tomassoni, killing him in a Roman street.

Whether this was a heat-of-the-moment murder is in question: duels were banned by Papal decree and it is suspected this was exactly that, but the fight was covered up by the pair’s seconds to protect all from further censure.

Caravaggio was fortunate in being protected by his talent. It meant he had friends in high places. Bringing him to justice was not straightforward, but he had to leave the Eternal City pronto.

An unintended consequence of the fight was the way it sent the artist off on an enforced journey into exile – and inspired a raft of his work.

Artists and their travels – and their travails, in Caravaggio’s case – is the topic of a new book by Highgate-based social historian Travis Elborough.

Travis’s previous works include his history of the Routemaster bus, the long player record, parks and pleasure gardens, spectacles and abandoned architectural oddities.

In The Artist’s Journey, he turns his attention to a selection of artists who have become synonymous with a place, or have found their canon expanded by movement, journeys and voyages.

“A change of scene and the chance to take in different surroundings and become acquainted with unfamiliar faces and customs can be a spur to fresh creativity,” he says.

“The journey itself, a stepping stone to going somewhere else artistically… painters tend to be peripatetic types. They are forever on the hunt for new things to commit to paper or canvas.”

Caravaggio’s case was one of forced exile, as Travis explains.

“Caravaggio was hot-headed and prone to pulling knives to settle disputes,” he writes. “But it seems more than likely now that Caravaggio and Tomassoni were fighting a prearranged duel.

“Duelling was a crime punishable by death in Rome, the tennis match was probably a cover story by their respective seconds to avoid censure.”

Girls on the Bridge, 1899, by Edvard Munch in Åsgårdstrand. [Incamerastock-Alamy Stock]

Caravaggio was given sanctuary by the powerful Colonna family and it was while he laid low at the estate, 20 miles from Rome, that he painted an image of David clutching Goliath’s head, and was seen as plea for clemency to Scipione Bhorgese, who oversaw Papal justice.

But as Travis explains, as well as powerful friends the artist had powerful enemies and it was deemed prudent that he put more distance between himself and the long arms of the law.

He headed south to Naples, then under the control of the Spanish kings. “Despite his status as a killer on the run, Caravaggio continued to be in demand as an artist,” he adds. He was commissioned to create a huge piece for a new church in the centre of the city.

Caravaggio could not hang about – fresh allegations revolving around him paying an assassin to do in an enemy meant Rome didn’t seem far away enough.

He headed to Malta, then essentially a heavily armed church-run island run by the Knights Hospitaller of St John Jerusalem. Perhaps he hoped by joining them he would be given a pardon. What Caravaggio did do was earn his keep by painting for the brothers, and held high hopes he might be accepted into the order, this putting him beyond the reach of the Pope. He eventually fell out with the monks and headed to Sicily, before ending up in Naples, here he died of a fever aged just 38.

Other artists have moved under a lot less pressure than the 16th-century purveyor of grandiose biblical scenes.

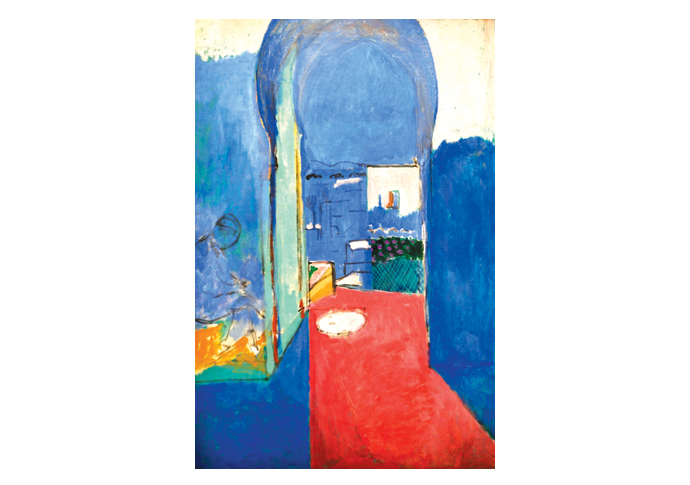

Travis considers Cezanne in Provence (as well as van Gogh in the same place), Dali in Manhattan, Katsushika Hokusai and his various views of Mount Fuki, Paul Klee in Tunisia, Turner in the Alps and Matisse in Morocco. Many were drawn by light, the thrill of discovery, and often, personal circumstances – trips abroad for the European artist could mean an affordable way of life, allowing them to concentrate on creating and not keeping food on the table and a fire in the grate.

Entrance to the Kasbah, 1912, Henri Matisse. [Agefotostock-Almy Stock]

For Claude Monet, a trip across the Channel led to him painting some of the best-known scenes of London ever committed to canvas. It wasn’t an artistic urge that saw him set up an easel on the Embankment – instead, it was the outbreak of the Franco-Prussia war in 1870.

Keen to avoid conscription, he headed to London and his stay saw him capture the city’s lifeblood, the fuel that drove the empire: the mighty Thames.

“Monet was drawn to London’s river front and its docks and bridges,” explains Travis. “During his stay he haunted the banks of the Thames and finished three studies.”

One was of the Houses of Parliament bathed in fog from Joseph Bazalgette’s recently completed Victoria Embankment. Monet was taken enough by the city to return three times 30 years after his first visit.

Artists travelling to new places also would break new ground in terms of style. One such trailblazer was Antwerp-born artist Alexander Keirincx, who was commissioned by Charles I to paint 10 views of his castles in Yorkshire and Scotland. The artist had finished four by the time the Civil War broke out.

“His pictures, shaped by the turn towards greater veracity in Dutch landscape painting, set new standards in realism,” adds Travis.

His skills as such mean that six centuries later, it is possible to pinpoint the spots he set up his easel.

Above all, Travis concludes that artists are drawn to places for many reasons – but once they are there, the chosen place becomes an unbreakable link to the work produced.

“A notable number here were drawn, like migrating birds, back to the same places over and over again,” says Travis.

“In due course that locale would then grow to become synonymous with the artist themselves or be seen in retrospect to characterise a key period of their output.”

• The Artist’s Journey: The Travels that Inspired the Artistic Greats. By Travis Elborough, White Lion, £20