Ernest James, barrister who had burning sense of justice

Rebel Labour councillor fought back against library cuts and the first redevelopment plan for King's Cross

Thursday, 12th June 2025 — By Dan Carrier

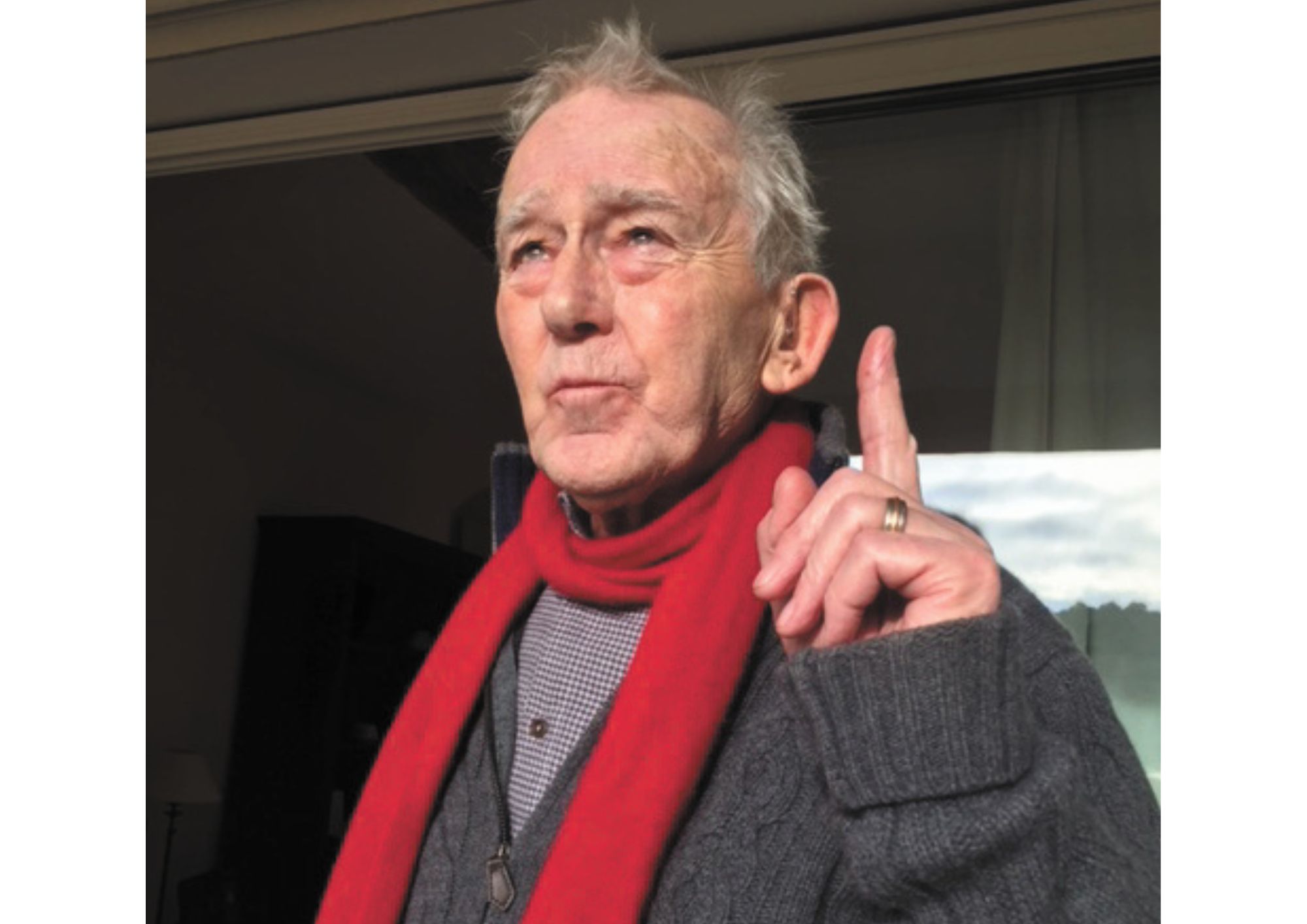

Ernest James

Ernest James would stride into court, ready to do battle for the person in the dock – always decked out in a pair of bright red socks.

But while his attire may have caught the eye in the serious setting, Ernest brought not just his sparkling legal mind to proceedings, but a burning sense of justice.

Ernest, who died on Monday aged 81, worked as a defence barrister and in his role as a Camden councillor helped steer the development of King’s Cross away from being a new Canary Wharf aimed at big banks and multinationals.

Ernest was born in 1944 in Bounds Green. His mother and father were originally from Northumberland.

Father Fred became an environmental health officer for Haringey Council, a role that included visiting houses and holding landlords to account. His mother Amy was a trailblazer – she worked for the civil service when it was expected for married women to resign their roles after their wedding.

She also bought a house in her own name with a mortgage – something that usually required your husband’s signature. She became a health visitor and worked in a doctors’ surgery.

His parents loved travelling to Europe and spoke the language Esperanto. It was a lively, politically informed atmosphere where values and ethics were important.

Ernest passed his 11 Plus, going to Wood Green Grammar, where he sat his A-levels.

In 1964 he started an undergraduate course in Business Studies at the Regent’s Street Polytechnic. He would recall The Who rehearsing in the Student Union basement

On graduation, Ernest landed a plum job for the Gas Council. These were the years of Harold Wilson’s white heat of technology.

The Gas Council were building the infrastructure that would pipe North Sea gas across the UK, and Ernest helped with the project of laying more than 800 miles of pipeline.

Later, in his role as a Camden councillor, he would bring such experience to bear on large-scale planning issues.

In 1970, Ernest went to Leeds University to train as a teacher – it was here he became involved in the student entertainment body, booking big name rock acts to appear at the university – and then taught business studies at the London College of Fashion in Oxford Street.

One of his students was the designer Katharine Hamnett – and the pair became firm friends.

It was during this time he moved to Belsize Park, settling in a house that he would stay in for the rest of his life.

While teaching, Ernest decided he wanted to study law and he embarked on a conversion course in the mid-70s at Gray’s Inn.

To help pay his way, Ernest bought a transit van and painted it in multi-colours. He did house clearances and then ran a stall at Portobello Market at the weekends, selling what he had picked up – he loved dabbling and it helped fund his studies.

Ernest had turned to the law as a natural extension of his strong sense of justice, linked to his politics.

A Labour member, he wanted to become a defence barrister – he would spend his law career focusing on defence work – and he was called to the Bar joining King’s Bench Walk and then the Bridewell Chambers in Gray’s Inn.

He would work there until he retired in his early 60s.

Ernest stood for election to Camden Council in 1990 and won a seat in Bloomsbury. His natural interests drew him towards housing, planning and licensing.

Ernest James with Paul Stinchcombe, the former Labour MP, as they tried to protect heritage railway buildings in King’s Cross from being knocked down

He would go on to serve two four-year terms in Bloomsbury, and a further four years for Somers Town, before stepping down.

His time as a councillor saw him stand up for what he believed in – sometimes in opposition to his own party. He had his wrists slapped more than a few times by the party whips for going off message but Ernest had a clear sense of what he thought was right and would not back down.

It was a barnstorming speech he made in the council chamber in the mid-90s that helped defeat a plan to turn the King’s Cross railway lands into a Camden version of Canary Wharf.

Ernest had watched with trepidation and interest as plans were put together to create an office-dominated development – and he was firmly against it.

His passionate speech brought many waverers along with him.

And Ernest was a great friend to the New Journal, and our late editor, Eric Gordon.

Ernest would always be available for a chat – and often he and Eric would delay the New Journal being sent to the printers for hours on press day as he shared a juicy piece of news that reporters would then be tasked to check out as deadlines came and went.

Ernest also was a key member of a council revolt against plans to close public libraries.

As cuts hit the Town hall budgets, plans were drawn up that would see a swathe of branches close altogether. Ernest argued that a Labour council should not be in a position where they were thinking closing a library was a solution.

As chair of planning, he brought a careful eye to proceedings, and then as chair of licensing, Ernest helped the council navigate new licensing laws that meant pubs and clubs could stay open all night.

He worked on licensing regimes that would balance businesses, culture and the wishes of residents.

And he stepped in when he saw an issue needed solving: once, as a licensing chair, he heard that venues in King’s Cross which were being used for Acid House parties, had turned the taps off in bathrooms so thirsty dancers had to spend money on overpriced bottles of water.

He got enforcement officers to visit the clubs and told them firmly their licence would be reviewed if they didn’t turn the taps back on.

Ernest was a brilliant host and raconteur – but if he invited you over for supper at his warm Belsize home, you’d have to be prepared to wait.

He loved cooking but it was also the process, oiled by glasses of good wine and great conversation: food would sometimes appear at midnight and he would declare it was perfect timing.

Ernest James in Italy on the day he married his wife Rhiannon

He loved cricket, reading political biographies, history and diaries, and visiting Italy: he made friends in Florence and loved the city so much that he and his wife Rhiannon married there in 2004.

He enjoyed a pint at the Steeles and the now-closed Haverstock pub, but didn’t frequent the Belsize café culture as he had a 50-year-old Italian coffee machine at home and felt no one could make it better.

In court, Ernest, the formidable defence advocate with trademark red socks, had a penchant for appearing 30 seconds before the judge called him forward – and then fighting for justice with a passion that impressed all in court.

As the New Journal can testify, it was good to have Ernest on your side.

His impact on both many individual lives, and the borough of Camden, is pronounced.