Eminent Victorians

The latest in this series of anecdotes relates to the American author of the Battle Hymn of the Republic, Julia Ward Howe; and her acquaintance with the poet Longfellow

Thursday, 20th November 2025 — By Neil Titley

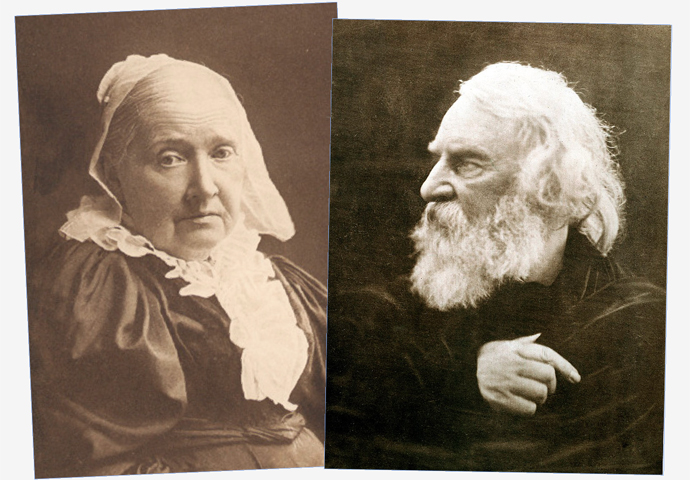

Julia Ward Howe in 1895 and Henry Longfellow in a 1868 portrait by Julia Margaret Cameron

ONE of the few certainties about the unpredictable Trump seems to be his apparent relish for the tourist version of Britain. This “teacakes at Windsor” delusion has long been shared by many of his countrymen.

After her marriage, Julia Ward Howe (1819-1910, author of the first – till 1931 – US National Anthem), chose to spend her honeymoon in London, and then touring England. She and her husband made many friends here, including Florence Nightingale (later godmother to one of their children). Julia became something of an Anglophile. “An English friend is a friend for life,” she once said.

However, Julia did not include the poet William Wordsworth in this category.

During the honeymoon, after a rain-soaked journey through the Lake District, punctuated by the exploits of runaway carriage horses (Julia: “I supposed the miseries of wet garments would soon be cancelled by that of a broken neck”), they arrived at Wordsworth’s house. Wordsworth had recently lost a lot of money speculating in United States bonds and was in no mood to humour Americans.

He ignored Julia and spent the evening complaining to her husband Dr Howe. “Incensed at this unusual neglect,” said Julia, “I made several interjections in a low tone – my husband allows me to swear once a week.”

When Mrs Wordsworth also began “to whine over their losses” and bemoan the fact that the Wordsworths should suffer for the misfortunes of another country, Julia made the acid observation:

“Why must you speculate in foreign stocks? Why did you not keep your money at home?” The Howes left amid a frosty silence.

Julia’s final barb was that the Wordsworths also “gave us a very indifferent muffin”.

The couple returned to work at Dr Howe’s Blind Institute in South Boston. It was to be a stable marriage, despite some discontent on Julia’s part. “For men and women to come together is nature – for them to live to together is art – to live well, high art,” she said.

They became friendly with many of the literary set of Massachusetts. Julia was amused by her first meeting with the notoriously shy Nathaniel Hawthorne. When they called at his house, Mrs Hawthorne called out: “Husband! Mr and Mrs Howe are here!” Behind her, they spotted the famous novelist sprinting across the hall and out of the back door.

When the Civil War began, Julia heard the tune of John Brown’s Body for the first time and said she was “mesmerised” by it. Soon afterwards, she lay half-awake in a hotel one night listening to distant guns. Julia remembered: “While waiting for the dawn, long lines of a poem began twining themselves inside me. I did not write them; they wrote themselves.”

Fearful of forgetting them, she scribbled the lines on the back of playing cards. The result was the lastingly popular Battle Hymn of the Republic.

She spent the rest of her life revered as the composer of these inspirational lines, but she also worked to promote higher education for women, and to aid the victims of oppression, particularly the Armenian people during the Turkish pogroms.

She almost welcomed old age: ‘‘Life is like a cup of tea; all the sugar is at the bottom,” she said.

One great friend of the Ward family was the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882), whom they nicknamed “Longo”.

Julia and her sister Louisa Ward found one aspect of Longfellow irresistibly funny – he wore a wig “of the most indescribable colour”.

At one dinner, Louisa could resist the sight no longer and suddenly burst into uncontrollable laughter. Longfellow politely joined in her mirth but kept asking: “What is so funny, dear Louisa?” The enquiry simply set off more guffaws. Louisa reported that finally “we both turned very red and ceased”.

During his 20 years of teaching European languages at Harvard, Longfellow wrote some of the most popular poetry in America. Such highlights as The Wreck of the Hesperus and Paul Revere’s Ride became standard favourites, but The Song of Hiawatha was the poem that sealed his success, selling over 100,000 copies in two years.

Julia Howe said that one of her acquaintances from the Far West told her that “if Longfellow had ever seen a Sioux Indian, he would not have written Hiawatha”.

Longfellow came to England in 1868 to receive honorary degrees from Oxford and Cambridge. Pressed about his impressions, he said that the thing he most admired about the country was Bass Ale.

When he was introduced to Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle, being a republican, he shook her hand rather than bow. He said modestly that he did not realise that he was so well known in Britain.

Victoria replied: “I assure you, Mr Longfellow, you are very well known. All my servants read you.”

He confessed: “Sometimes I wake up at night and wonder if it was a deliberate insult.”

After his death, the British paid him the honour of being the first American to have a memorial bust in Westminster Abbey’s Poets’ Corner. His literary reputation on the other hand slumped immeasurably, one critic writing: “Longfellow is to poetry what the barrel-organ is to music.”

• Adapted from Neil Titley’s book The Oscar Wilde World of Gossip. www.wildetheatre.co.uk – available at Daunts, South End Green