Eco 2023: The Golden Mole – and why this planet is worth fighting for

Author's warning of the 'litany of mistakes' we've made in relation to the natural world

Friday, 6th January 2023 — By Anna Lamche

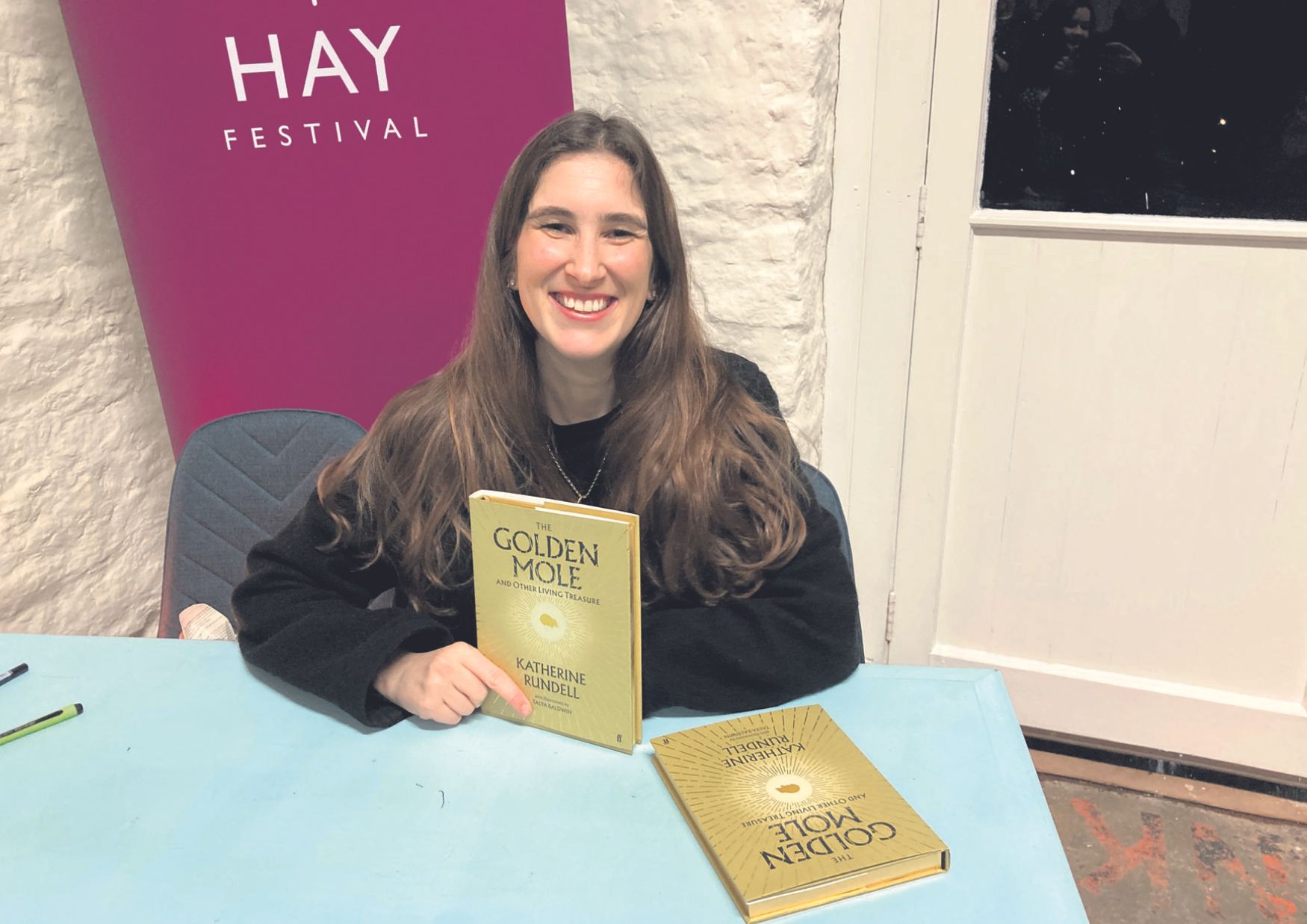

Katherine Rundell lives in Primrose Hill

AS wonderful and strange creatures pass into extinction at a rapidly increasing rate, an author has warned we must recognise “the munificence of what we have” before it is gone.

Katherine Rundell, from Primrose Hill, told the Hay on Wye Winter Festival that her new book, called The Golden Mole: And Other Living Treasure, is a “salute to the living world”.

A series of short essays on animal life, Ms Rundell said her criteria for selecting the creatures featured in the book were those which are “endangered or threatened”.

“That unfortunately narrows it down almost literally not at all. There is almost no living thing… for which there is not a subspecies that is at risk of extinction,” Ms Rundell said.

Featuring animals like the wombat, the Greenland shark and the narwhal – along with more familiar species like the crow, the hedgehog and the giraffe – The Golden Mole is an exploration of “the biological reality of these creatures” as well of “the litany of mistakes that we have made” in relation to the natural world.

“Often we use [animals] to lay out our ideals and our hopes. And then of course, there’s also our rank stupidities – a lot of the book addresses the amount of death that we have created,” she said.

“In some ways a subtitle for the book would have been ‘love and error’: the ways that we have been so hungry for the living world, the ways we have cherished it, but [also] the ways we have destroyed it,” the author said.

According to Ms Rundell, “the book started as these essays which were a bid to say: would you look at what there is around us, would you look at the munificence of what we have?”

The essay from which the book takes its title explores the secret life of the golden mole, a small burrowing mammal found in Sub-Saharan Africa.

“A friend told me about their existence – the fact that they are the only iridescent mammal. Iridescent as in under the light they change colour, they change blue, gold, red,” Ms Rundell said.

While most iridescent creatures, like birds and butterflies, use their colour-changing capacities to communicate, “the golden mole is blind. Its iridescence is not useful. It’s a byproduct of evolution. It’s one of those sparks of beauty thrown out – beauty without purpose. And I love that,” she said.

Another of Ms Rundell’s “favourite” essays focuses on the Greenland shark, one of “the oldest” living creatures on the planet.

“We know almost nothing about them because they swim eight Eiffel Towers deep. But recently, a number of them were caught and it was reckoned that they would probably be around between 300 and 515 years old,”she said, adding that some are believed to be “in their sixth century”.

“While John Donne was there writing about love and death and plague, a Greenland shark swam through the waters beneath him. And its parents would have been old enough to have lived alongside Boccaccio, and its great-great grandparents alongside Julius Caesar,” Ms Rundell said.

In the course of researching the book, Ms Rundell said she was regularly surprised by the brilliance of animal life.

“[Animal] intelligence is astonishing, and one of the things that the book sort of harks on is this idea that so rarely have we discovered that we overestimated the intelligence of a living thing. So often it is that we discover that we have wildly underestimated the complexity of a living creature,” she said.

One example is the octopus, which is “the closest thing to alien intelligence” known to man, Ms Rundell said.

The cephalopods have “a very rich intelligence that is so far from the way our intelligence is formed that we have no real space for it cognitively in our own imaginations”.

Ms Rundell said in writing her book she attempted to resist anthropomorphism – the attribution of human traits, characteristics or emotions to non-human beings – insisting instead on the “unknowability” of animals.

“How does one hold in one’s head passion and love for these things, and also a stern remembrance of that unknowability?” she said.

According to Ms Rundell, the book is ultimately about paying “attention” to the world around us.

“I love the idea that attention is something vivid and political, that at its finest – as Simone Weil says – attention is the rarest and purest form of human generosity,” she said.

“Our active, political, forward-moving attention, I think, is one of the things that is hardest to hold. There are many people with a vested interest in your acquiescence to their wish that you look away.

“And this is the moment that we are living through, alas, in which refusing that acquiescence and keeping the full blast of your focus – that’s a valuable political thing… It is an act of resistance.”