Drax of Drax Hall story casts light on role of slavery in British history

\Reparations are about recognition and redemption and that must happen'

Tuesday, 24th June 2025 — By Dan Carrier

Sugar processing on a plantation

A new book by Professor Paul Lashmar traces a family’s links to a Barbados plantation, and calls for an honest conversation about the impact of slavery, writes Dan Carrier

EVALUATING carefully and considering calmly our nation’s history is vital to creating a better Britain today – and that means being honest about the impact of the slave trade socially, culturally and economically, says a new book about one of the UK’s wealthiest landowners.

Professor Paul Lashmar, who teaches journalism at Islington’s City University, has recently published Drax of Drax Hall – a book that considers an English family who established a sugarcane plantation in Barbados in the 1600s using chattel slavery.

Today, the former Conservative MP Richard Drax is a wealthy landowner whose family fortune began in earnest on a Caribbean plantation where a brutal chattel slavery was enforced.

Paul uses the Drax family story as a prism to cast light on how Britain today looks at its past and the role slavery has played over 400 years of history.

Paul has a long-standing interest in telling stories that delve into our past. One motivation has been considering truths he had been fed at school – and a journalist’s urge to fact-check.

“I realised, as a child, I was pumped full of jingoistic history,” he says. “Much of what I was taught was designed to say how wonderful Britain was. A failure to tell our history honestly has left us today in a dire state.”

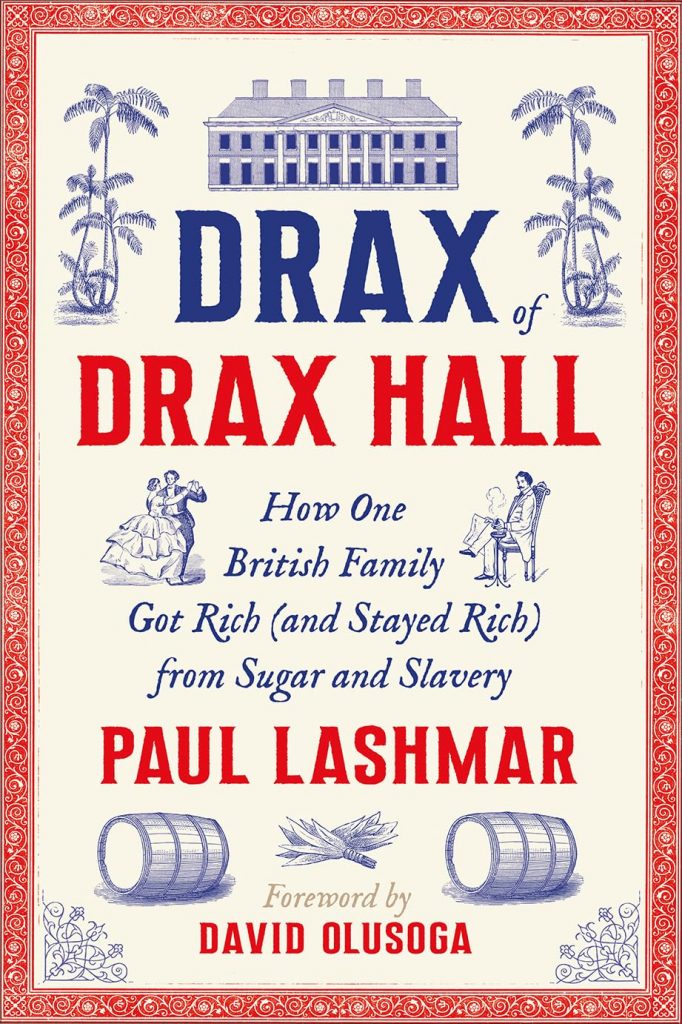

Paul Lashmar’s new book

The Drax story starts centuries ago and Paul’s forensic study into the basis of a family’s fortune considers where power lies in the UK today.

“There was always an acknowledgement we were involved but it was pitched that we, Britain, were all about abolition – that we abolished slavery and that there were 150,000 freed people because of the work of the West African Squadron,” he says.

“But that narrative doesn’t reflect the fact we were part of a trade that shipped over 12 million African people to colonies. I do not think that has been ruminated on enough, certainly not until recently.

“The UK has to reflect our society is part of the legacy of slavery. That is an inescapable fact. People may not have a legacy of families who were involved directly in slave ownership, but the colonial economy the UK as a whole benefited from financially was built on it.”

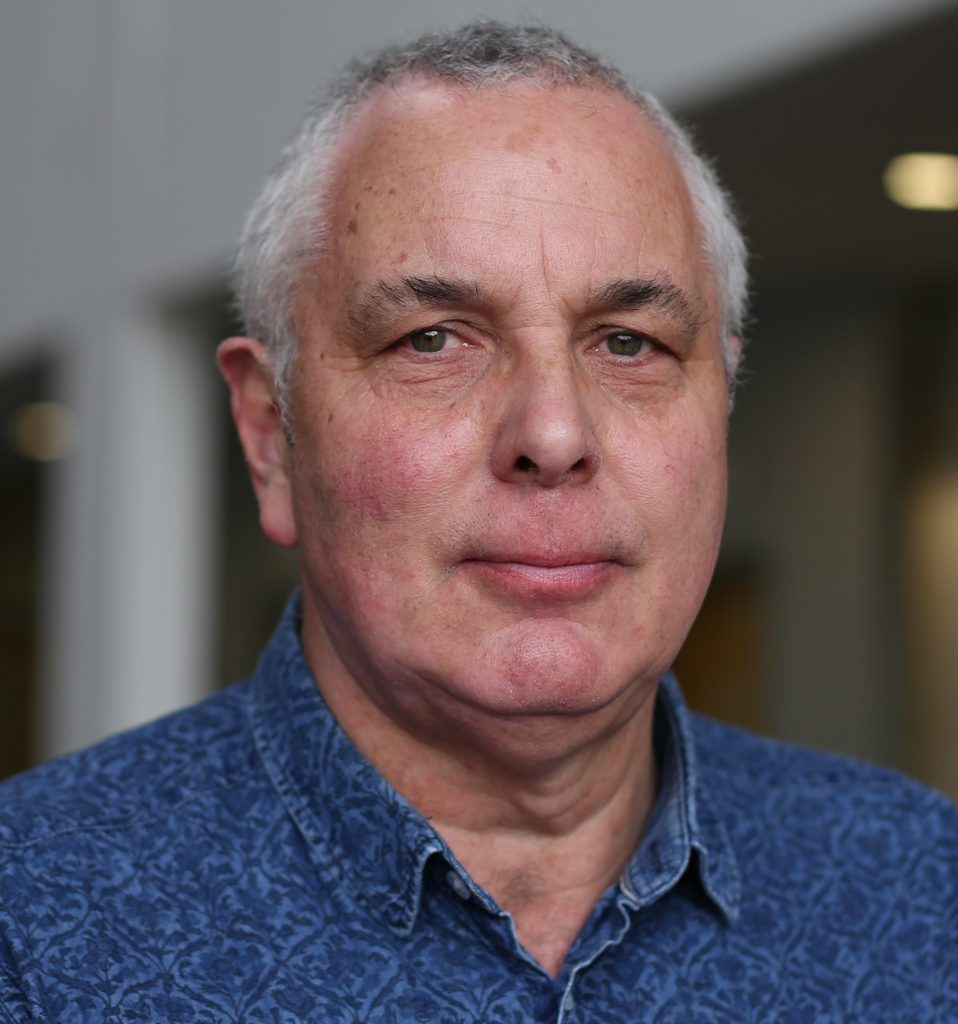

Paul Lashmar [Bill Evans]

Those who would prefer to either ignore historical truth or pass it off as something in the past and therefore not relevant today disregard our past and its impact on us.

“Some may say, why rewrite history? But history is to be considered every single day – it is about finding out more, reinterpreting what we know,” he says.

In 2012 came the outrage over the killing of George Floyd in America – an incident that prompted a period of introspection about racism in our society.

In Bristol, the statue of slave owner Edward Colston was taken down and thrown in a harbour. Britain was asked to look at its past and the results showed divisive opinions. Commentators pontificated on what it all meant.

As Paul drove down the A31 in the West Country, with the radio news talking about the day’s events, he passed what is called The Great Wall of Dorset.

“As a journalist, there are always times you have a lightbulb moment with a story. For me, it was driving past Charborough Park and thinking about the Black Lives movement,” he reflects.

It’s a long piece of brick work and on its enclosed side is the Drax estate.

“At the time, I knew little of Richard Plunkett-Ernle-Elre-Drax, except he lived in the park, was a Dorset MP for the Conservative Party, and his ancestors had somehow been involved in slavery,” he says.

He began looking into who Drax was, what he believed and how he felt about his ancestors’ past and how they had made their fortune. “Drax has rarely commented on his own ancestors’ history of owning hundreds of enslaved people over 200 years,” he says. “Richard Drax, as an MP, had been forthright on many other subjects in his columns, on his blog and in the House of Commons.

“Back in 2012, the Dorset Echo reported Richard Drax had issued a stark warning on immigration, insisting: ‘I believe, as do many of my constituents, that our country is full’.

“When I read about Richard Drax, who had been an MP for 10 years, I was astonished no one had done a fourth estate audit – when you look at some rich and powerful and you look at what they do, how they do it, and who benefits.

“I wanted to see how a story about British history could be told through it.”

Drax was a member of the European Research Group, the Brexiteers who have had a huge impact on the UK in recent years.

“The ERG was the tail that wagged the dog of the Tory party for two decades,” says Paul. “The further I went back, the more fascinated I became. These characters shone a light on events in British history from the 16th century onwards.

“What is so remarkable about this story, is not only are they the story of a family who were settlers there right at the start of empire, they started the growing of sugarcane commercially, and implemented chattel slavery – they are the only family who, 400 years later, still own the plantation. It is completely unique in that way.

“I thought, this is a great way to explain something about our country. I could follow the lineage. It asked the question: why are some people wealthy, and others not?

“It is a family that allows us to explain the landed gentry’s rise to power and how they have used that power over 500 years. Their story is atypical of the landed gentry in the UK – they have been MPs, JPs, sheriffs, they have held the levers of power, so the question is, how have they used them?”

As well as the story of plantations, of wealth funnelled back to Dorset, of enclosures across their estates that changed the relationship between landowner, farmer and agricultural worker, the book reveals how the family have witnessed key moments in British history.

“General Thomas Earl, for example, was an extraordinary commander who fought at the Battle of the Boyne,” says Paul.

“He was at the centre of a highly symbolic event that marked the relationship between Britain and Ireland. And James Drax, who first established the Barbados plantation, was fascinating – a settler who made a lot of money, and came up with the concept of chattel slavery. There is a sense of duty, too – many have served in the military and put their lives at risk. The landed gentry lost many in the First World War. They felt it was their duty. It is a complex picture.”

The former MP has not commented on the book. But others whose ancestors have been involved in slavery have sought to acknowledge the past.

Filmmaker Alex Renton, the Gladstone family and the journalist Laura Trevelyan have all looked at the roles their families played in the slave trade and acknowledged what happened. For the island of Barbados, this is not something that happened long ago and therefore irrelevant today.

When Richard Drax’s father Walter died in 2017 – while Richard was still a sitting MP – the plantation land was passed down to him.

Then, the Barbados government’s minister for housing was looking for sites to build much-needed new homes, and they considered a place called Drax Hall, on the estate, for compulsory purchase – 51 acres of the former slave plantation. It would have seen the Barbados taxpayer hand over something a little more than £3m for the property. Paul wrote about it for The Observer.

Former MP Richard Drax

“Two days later, the Barbados prime minister said they had put the deal on hold,” he says. “There was a big pushback by people who feel reparations should be paid.”

Paul quotes Sir Hilary Beckles, who leads reparations for CARICOM, who said the Drax plantation remains “a massive killing field with unmarked cemeteries”.

How should an individual feel, knowing that their inherited wealth was created this way?

“The family received a huge figure in compensation when slavery was abolished,” he reflects. “It is not like slavery just stopped in 1834. People from the Caribbean background feel it, the impact on culture and its continuing relevance needs to be recognised.”

Economists have tried to put a figure on the profits and costs of slavery.

“The idea that Britain is going to hand over around £2trillion – the cost some have estimated – is unlikely,” adds Paul.

“But it is down to individuals, and society as a whole, to recognise the distress slavery caused, and do things to recognise the 200 years of forced labour that helped to make us a wealthy country. It was a triumph of economics over ethics. Recognition is part of the process. Some reparations are not to do with money.”

And Paul points out when Britain outlawed slavery, it paid slave owners.

The figure was so high it cost 40 per cent of the national debt at the time, and there is an interesting quirk of language that resonates today.

“Slave owners said it was reparations,” he reveals. “Today, people have been upset by the call for reparations to be paid, but reparations were paid in the 1830s.”

Above all, Paul’s book calls for an honest conversation about what happened and a facing up to responsibility and impact of the slave trade.

The Drax Hall house in 2019

Paul quotes Sir Hilary again: “The legacies of slavery continue to derail, undermine and haunt our best efforts at sustainable economic development and the psychological and cultural rehabilitation of our people from the ravages of crimes against humanity committed by your British state and its citizens in the form of chattel slavery and native genocide.”

Paul says what he thinks feels unimportant next to Sir Hilary’s views, but adds: “. The problem for those from whom reparations are asked, is that it takes the power and agency away from them and puts it in the hands of those who once had no power.

“If Britain is ever going to re-establish its moral leadership role in the world again as an outward-looking, democratic and progressive nation, it needs to come to terms with its past.

“Pretending that hundreds of years of enforcing slavery in the colonies is all the distant past and has no consequences or debts in the present is foolish.”

Drax of Drax Hall: How One British Family Got Rich (and Stayed Rich) from Sugar and Slavery. By Paul Lashmar. Foreword by David Olusoga. Pluto Press, £25

Event: Poetry: Britain’s Legacy of Slavery in Barbados. An evening with Esther Phillips, Poet Laureate of Barbados, and Paul Lashmar author of Drax of Drax Hall: How One British Family Got Rich, at the Frontline Club, 13 Norfolk Place, W2 1QJ. June 24, 7-8.30pm