Cultural exchange: how Hawaiian treasures came to Bloomsbury

A new Hawaiian exhibition at the British Museum illuminates the fact that European explorers’ voyages were not one-way journeys. Dan Carrier reports

Thursday, 19th February — By Dan Carrier

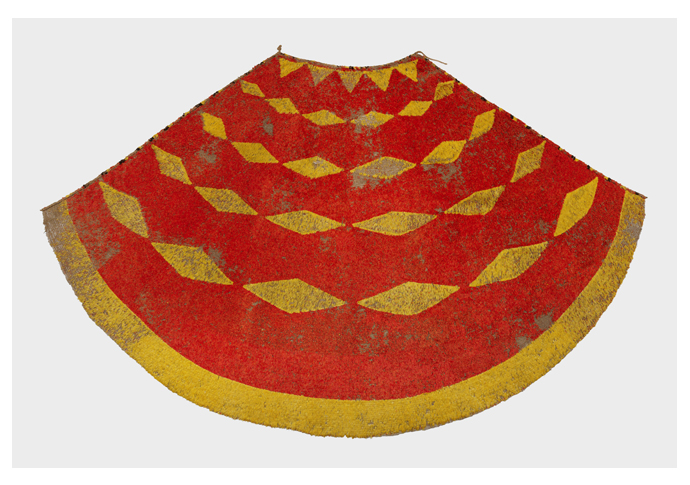

The ahu ’ula (feathered cloak) gifted to George III [Image: Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2025 – Royal Collection Trust]

IT is a stop-you-in-your-tracks moment: the extraordinary story of a Hawaiian monarch’s journey to Georgian London 200 years ago at a British Museum exhibition is a captivating tale.

Hawai’i: A Kingdom Crossing Oceans is a show created in conjunction with Native Hawaiian knowledge-bearers and, through a rarely seen collection of Hawaiian treasures, we learn of how these artefacts came to Bloomsbury and what they mean today.

It tells the story of how King Liholiho (Kamehameha II) and Queen Kamāmalu travelled thousands of miles across oceans to meet George IV and would meet a tragic end on this royal tour. They caught the measles and died – but before their demise, they had come to the very place you are standing now and looked at the very same objects.

It is an eerie experience to think the people whose lives we are learning about through these artefacts had been here, in the British Museum, as guests of George IV – and is a good example of how the exhibition illustrates a new way of looking at the museum’s objects and artefacts.

Dr Alice Christophe is a curator, and oversees the museum’s Oceania collections, spanning the Pacific region.

Kamehameha II in a hand-coloured lithograph by John Hayter, 1984 [The Trustees of the British Museum]

In 1824, King Liholiho and Queen Kamāmalu set out from Hawaii on a goodwill journey.

“They travelled to the UK and asked for an audience,” says Dr Christophe.

“As part of our research, we discovered where they had been. They had come to the British Museum during their stay and saw objects on display that are on display today.”

Why did two nation states thousands of miles apart embark on this friendship?

The archipelago had been settled around 1,000 years ago – Polynesian sailors used the stars and migratory birds to navigate their way there – and it came to the attention of the British when Captain James Cook died on a Hawaiian shore during a voyage in 1778-1779.

In 1810, the first monarch to unite the islands, Kamehameha I, sent a giant feathered cloak to George III with a letter.

“It was as foreign powers were coming to the islands, things were changing and a month before he unified the islands he reached out to George III, sent gifts and from this, a royal delegation came to London to seek an alliance and protection from the Crown,” explains Dr Christophe.

Kamamalu. Hand-coloured lithograph by John Hayter, 1984 [The Trustees of the British Museum]

The eye-catching feathered cloak, called a “ahu ’ula”, came with a written request asking for an alliance and protection from the British. It led to the visit in the 1820s.

“This royal visit was the first time the royal couple had gone to a foreign land,” explains Dr Christophe.

“Just think about these monarchs travelling all this way, adapting to a new, cold city. It is incredible how it unfurled.”

The British took care of their visiting dignitaries: Foreign Office files show that when they landed in 1824, they were inoculated against smallpox. They stayed in Charing Cross and were given the full royal treatment of banquets and guided tours.

But the trip would end in tragedy when the pair contracted the measles, for which there was no vaccine, and died. Their bodies would be returned for burial in Hawaii.

“The Foreign Office had the difficult task of sending a letter informing the Hawaiians of the deaths of the King and Queen. There had been several months between them passing and the letter reaching Honolulu,” adds Dr Christophe.

A mahiole hulu manu (feathered helmet) [The Trustees of the British Museum]

“The news reached the islands around a month and a half before their bodies arrived home.”

The exhibition has a wider context.

“This story is grounded in ancient movements and the ocean as a freeway – the sea was not seen as a barrier but as a means to develop relationships across the Pacific,” says Dr Christophe.

The Oceania collection is made up of around 55,000 items, 1,000 of which focus on the Hawaiian archipelago.

“They are both historic and contemporary,” says the curator. “It is one of the largest collections outside of Hawaii and it is a significant responsibility. We have worked closely with people in Hawaii to re-shape our understanding.”

Using the 200th anniversary as a hook, the exhibition shows that traditional ideas of European explorers voyaging across the planet as something of a one-way journey are simply not the case.

Silver teapot presented to Kuhina Nui (Premier) Ka’ahumanu [Burnice Pauahi Bishop Museum]

“We have looked at collections from that perspective of navigators or explorers going across the vast oceans – the story of Cook and British naval officers, for example – but not got the story of these reverse journeys.

“It shows the relationship in a new way and gives agency to the people who came this way. And at its core, it tells the story of the deep and layered relationship between Hawai’i and the United Kingdom, reflecting on care, sovereignty, and the complexity of allyship.

“We hope this show will spark conversations and uplift people in the archipelago and beyond.”

• Hawai’i: A Kingdom Crossing Oceans runs until 25 May in The Joseph Hotung Exhibition Gallery (Room 35), at the British Museum