Cover notes

The name James McConnell is not a household one. But if you were a pulp fiction fan in the 1950s you’d certainly recognise his work. Dan Carrier turns detective...

Thursday, 27th June 2024 — By Dan Carrier

“THE shot ripped a ragged hole through the stillness, its sound near enough to strike physically against him…”

These are the opening lines of Trail Smoke, a pulp Western written by Ernest Haycox and published in the 1950s.

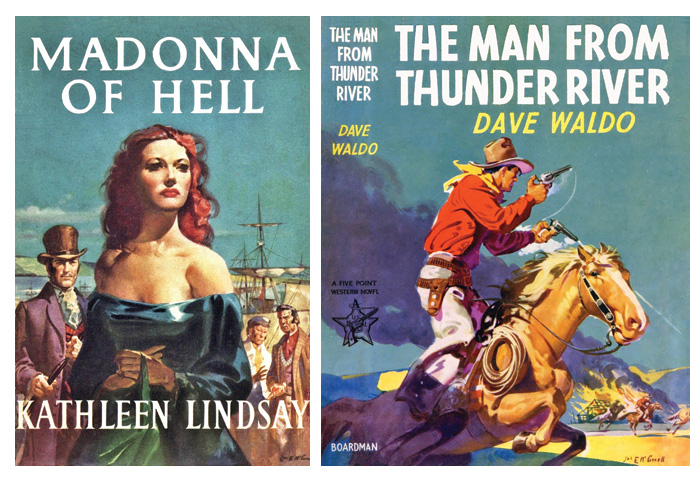

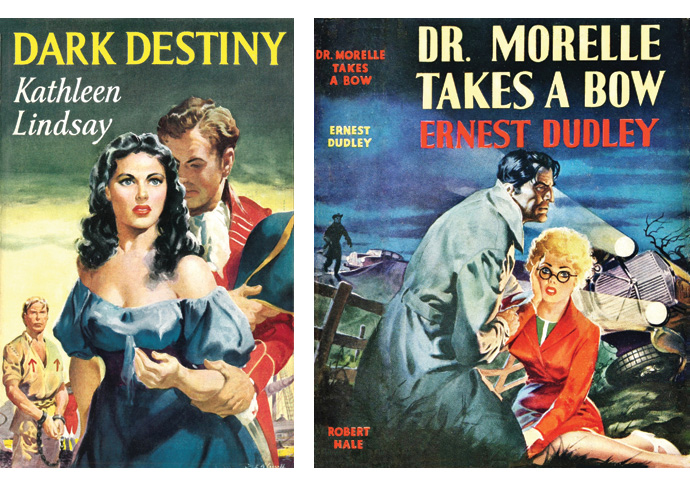

And while the stories of heroic cowboys and dastardly indigenous peoples (though sometimes as heroic as the white man) ran along well-worn plot trails, there was an accompanying visual art that sold the tales inside.

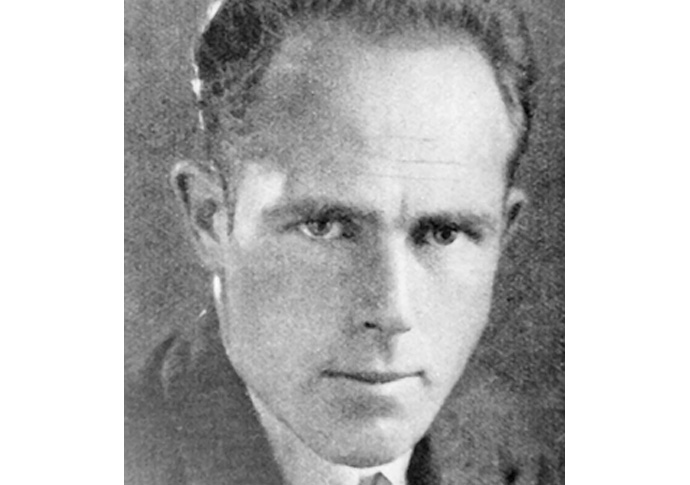

And the man responsible for the majority of the covers of the many thousands of cheaply printed, cheaply sold Westerns and other novellas that were the staple of shops in mid-20th century Britain, was an artist called James McConnell.

Now a new biography of this highly successful commercial artist, whose work created a genre and is instantly recognisable but whose name is hardly known, shows quite how seminal McConnell’s work was.

And much of the amazing imagery comes from the collection of a retired Bloomsbury postman.

Jim Crealy was attracted to McConnell’s artwork as a child.

A Wild West annual given at Christmas in 1960 had a striking cover design by McConnell. Little did the nine-year-old know, the day he opened his present would be the beginning of a lifelong love of collecting McConnell covers.

After leaving school, Jim worked for a firm selling ladies underwear, had a stint at an insurance firm and eventually became a postman, based at the West Central Sorting Office in Bloomsbury. Now retired, he has the most comprehensive collection of the McConnell archive known.

He remembers as a primary school boy eagerly awaiting each week the publication of titles such as The Beano, The Dandy, Hotspur, Beezer and Topper.

But his first real collection came a long way.

“There were a series of Superman comics in black and white that had been reprinted in Australia,” he recalls.

“They sold for 6d. There was a firm in Islington that had a deal with the Australian company. They had a contract to reprint the American comics and bring them over here.

“I started my collection by swapping titles with friends. I’d offer them a copy of The Beano or The Dandy.”

He then found what would become a mecca – a second-hand bookshop called The London Lending Library.

“It was owned by a man called Mr Puddy, and for 6d a week you could borrow a book.

“He had had the shop since at least the 1930s and among the titles, he had a huge range of novels illustrated by McConnell.”

Jim was a keen Western fan and recognised how the artist drew on Hollywood classics for inspiration.

“I’d watch them at the pictures,” says Jim. “I loved how he saw Westerns.

“He was inspired by the likes of John Ford. One image looks exactly like a scene featuring Gary Cooper and Grace Kelly in High Noon. He must have seen the film, and I suspect he had a photographic memory as his works are often very similar to classic moments in movies. His ability to capture scenes was simply extraordinary. They have that Hollywood vision and attract the reader’s eye.”

Jim owns hundreds of his works – and no one quite knows how many McConnell painted.

“He did so many, people are still finding new ones that have been forgotten.”

Biographer Steve Chibnall says McConnell used zesty images that would draw the reader in with the promise of something racy.

“McConnell liked to think of himself as an action painter – not the kind who threw paint on canvas and then wheeled a bike over it to emphasise the process of artistic labour, but the kind who could create the illusion of movement in a tableaux,” adds Mr Chibnall.

His paintings might not have made it onto a gallery wall until 1976, five decades after his extraordinary stream of production began, yet he is one of the most exposed artists the UK have ever produced, with his work on every news stand and bookshop.

“His commercial art ranged through sales brochures to adverts, jigsaws and toy boxes, film posters, estate developers, illustrations and more than 100 magazine front covers,” says Chibnall.

The pair spoke before McConnell’s death in 1991. The artist had a workbook that held commissions since he began as a freelancer in 1933, presenting an accurate idea of scale of his output.

“He read the books that he was asked to summarise in his cover paintings. Using his vivid imagination, he would visualise a scene and authenticate its details by drawing upon a wide range of reference material from the libraries in the art departments of publishers such as Pan and from the American and British weekly magazines and the monthly Western-story pulp that he bought regularly.”

McConnell was born in the north east and headed to London aged 21 to work for John Swains’ Blockmakers, based in Farringdon and Holborn. He worked creating adverts for items such as Pears Soap.

James McConnell

He also enrolled on a night class at St Martin’s in Charing Cross Road to hone his work as a commercial artist and then entered the world of the freelancer.

Through the 1930s and beyond, he rented studios within walking distance of Fleet Street and Bloomsbury – giving him easy access to the newspaper and publishing industries.

Based in Rosebery Avenue and Great Russell Street, McConnell received commissions worth up to eight guineas per piece. It came to about an average week’s wage for what was two days’ work.

Detective novels were popular in the 1930s – murder mysteries comprised 25 per cent of all books published – so as well as the Western, he would create moody shots of men in trilbys clutching revolvers.

“McConnell’s work was largely sympathetic to Native Americans and their struggle to resist the expansionist settler state and its professional army,” adds Chibnall.

“His braves and their leaders were proud and fearless and are strongly individual within their warlike ‘type.’

“Remarkably for someone who probably had never met a North American aboriginal, his ‘indians’ seem closely observed and finely detailed.”

Historical romances meant everything from hunky Roman centurions carrying toga-clad damsels through to the chisel-jawed sharp suit-wearing man clutching a woman to his chest.

“If you were a publisher’s art director in the three decades after the Second World War, and you were looking for cover illustrations that would inspire readers seeking an exciting and perhaps escapist story, McConnell offered a one-stop shop. Few competitors could summon up a sense of action quite so convincingly as McConnell, who could also offer flawless authenticity for historical settings,” adds Chibnall.

McConnell died in 1991, having retired over a decade before. He spent his retirement painting for pleasure – landscapes and equestrian scenes, as, perhaps unsurprisingly, horses remained a favourite topic.

• Miniature Marvels: The Book-Cover Art of James E McConnell. By Steve Chibnall, Telos Publishers, £25