Brogue nation

Close to home but not at home, Irish culture has had a huge influence on London, writes Dan Carrier

Thursday, 13th July 2023 — By Dan Carrier

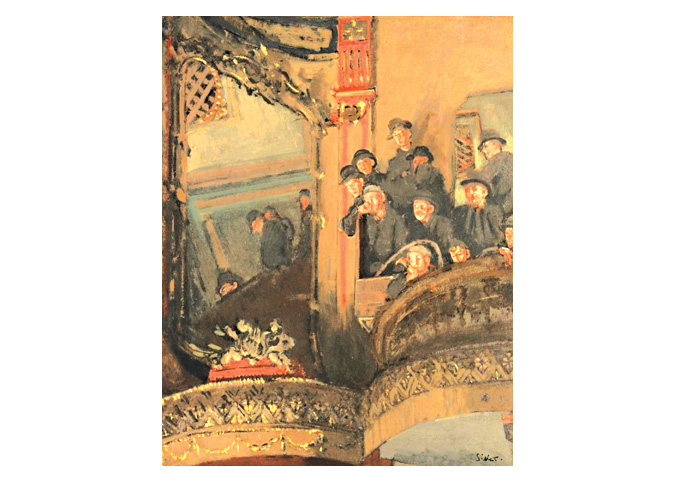

Walter Sickert’s painting of punters in the gallery of the old Bedford Theatre in Camden Town

THE letter to The Times smacked of last-straw desperation. Dated Tuesday, July 3, 1849, the writers – signed by more than 50 people – begged for London to sit up and take notice of their plight.

They described themselves as “livin (sic)… in muck and filth.

“We aint got no priviz, no dust bins, no water-splies, no drain or suer in the hole place. The Suer Company in Greek St, Soho Square, all great, rich and powerfool men, take no notice of our complaints. We all of us suffer, and numbers are ill…”

This cry came from the depths of the notorious St Giles Rookeries and gives an insight into life for some in the capital.

The letter is quoted by Professor Richard Kirkland, who teaches Irish literature at King’s College London, in Irish London: A Cultural History.

Prof Kirkland considers how in the years following the famine, London became a city with more Irish people than many cities in Ireland, and from this migration emerged a culture with many strands. The author seeks to identify the key elements and discuss their growth.

His work ranges from the newly arrived poor to purveyors of Irish-influenced literature and other arts.

The Rookery, at the southern end of St Giles in the Fields parish, was in the mid-1800s the most notorious Irish district in London. Covering eight acres, its tangled mass of alleys were perpetually collapsing, “its courtyards and houses medieval and impenetrable, one great maze of narrow crooked paths crossing and intersecting in labyrinthine convolutions”.

It had become a port of call for Irish immigrants – partly because the people living there were known for their generosity. Migrants could always find a welcome and space to lie down.

Prof Kirkland’s study begins from 1850 – and he cites historians Sheridan Gilley and Roger Swift, who identify the largest proportion who escaped the famine were poor who left behind a “rich Gaelic language and culture,” coming to a city where this inheritance “had no meaning and no encouragement to survive”.

It was not an easy move: “Disliked for their politics, their religion and their race, they were in Britain as exiles in Babylon,” add Gilley and Swift.

The book’s expansive research and richly detailed storytelling comes at the topic from a number of angles, from the plight of post-famine immigrants to the contribution of an Irish intelligentsia.

As Prof Kirkland states: “Although a subject such as Irish London might initially appear to speak of a clearly demarcated constituency and thus offers itself as a story to be told – a self-contained narrative with clear boundaries – the reality is inevitably other than that; the Irish in London were never one thing, and were never organised around a single political or cultural issue.”

Professor Richard Kirkland

Migrants faced many psychological issues that hampered integration. There was the fact they were close to home but not “home”, a sense of disappointment for those who had originally wanted to migrate to America, a refusal to accept their exile was permanent and an ambivalence towards the UK government: “A sense of obligation of gratitude was nullified to a considerable extent by their belief that it was Britain’s misgovernment of Ireland had caused them to be uprooted in the first place,” writes the author.

Prof Kirkland describes new ways of coping, thriving, and making an impact.

“It is not difficult to find evidence of Irish cockney activity that contradicts hostile accounts,” he says.

“Many second generation London Irish were active social organisers and were energetic in pursuit of better living and working conditions.”

And they would play major roles that helped define British working-class struggle.

“Irish areas were distinguished by a strong sense of community and a commitment to mutual care,” he writes. “This ranged from whip rounds for funerals, lending money and goods, taking in orphans and help finding work.”

And it translated into social action. In the summer of 1888, young Irish women take the lead in the “Match Girls Strike” at the Bryant and May factory in Bow.

The working conditions saw 1,400 women walk out – and were galvanised by the work of Anglo-Irish journalist Annie Beasant, whose articles included a piece called “White slavery in London,” that caused uproar.

It was a landmark moment in British industrial relations. A year later, a dock strike led by Irish trade unionists further cemented an idea of social co-operation to improve lives.

“In short, the desperate necessity for hospitality that life in the St Giles rookery demanded continued to resonate in the historical memory, emphasising the centrality of endurance, resourcefulness and community,” says Prof Kirkland.

From the 1870s, while the majority of migrants remained unskilled, there was a growing trend for Irish school teachers and civil servants. There was also a lure for “middle-class arrivistes”.

“The reasons why ambitious writers wanted to come in the 1870s and 1880s were compelling,” he writes. “London offered a vast market.”

George Bernard Shaw is one example, leaving Dublin in 1876.

“Every Irishman who felt his business in life was on the higher planes of the cultural professions felt that he must have a metropolitan domicile and an international culture; that is, he felt his business was first to get out of Ireland. I had the same feeling,” Shaw would say.

By 1872 every London paper had a staff with Irish writers – and Prof Kirkland reports how they were seen as the best in the newsroom.

“Fleet Street was greatly enriched by this,” he writes.

On such journalist was Robert Lynd, who moved to London in 1902.

“Lynd’s house in Hampstead became a centre of cultural activity and more covertly political mobilisation,” cites Prof Kirkland.

“He delivered classes for the Gaelic League. He knew everyone of influence – for example, James Joyce, who held his wedding reception in Lynd’s house in 1931.”

The cultural revival saw literary groups blossom – one being the North London Irish Literary Society, based in Camden Town.

It was not just literature but dancing and music, too: St Patrick’s Day, 1906, saw the Royal Opera House sold out for Irish music shows.

Popular performance had a strong influence. Prof Kirkland considers, for example, the Walter Sickert painting of Little Dot Hetherington at the Bedford Music Hall in Camden High Street.

The painting includes a character waiting in the wings, an Irish Cockney singer called Bessie Bellwood.

Born Elizabeth Mahoney in Cork in 1857, she was brought up in Bermondsey.

“Her popularity was not based on the suppression of her cultural inheritance but rather its overt celebration,” says Prof Kirkland.

“She would say: ‘I’m Irish in spite of my English accent and I am just as proud of the old country as I would be if I had a brogue a foot and a half thick.’”

• Irish London: A Cultural History 1850-1916. By Richard Kirkland. Bloomsbury, £28.99