Bombs and books: ‘The Pope of Russell Square’ during the war

Peter Gruner reviews the updated letters of TS Eliot

Friday, 30th January — By Peter Gruner

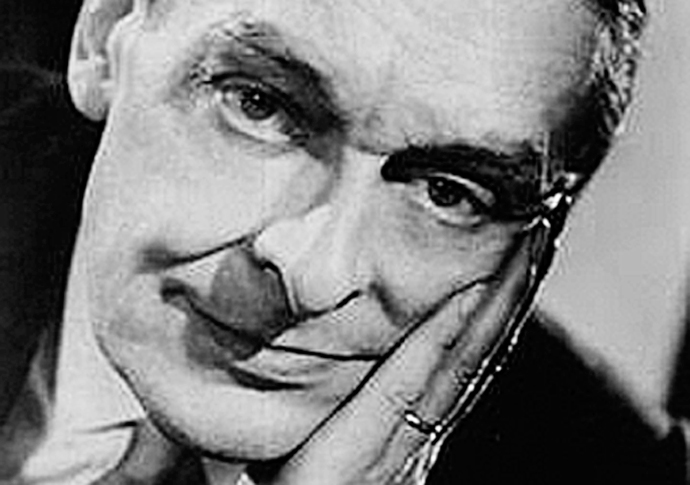

TS Eliot [Ellie Koczela_CC BY-SA 4.0]

HE was in his mid-50s, tall, sleek and distinguished looking – but one of the world’s greatest writers was becoming increasingly nervous as bombs dropped near his office and home in Russell Square during the Second World War.

TS Eliot worked from his temporary home and office in the Square and took it upon himself to try and sustain the literary life of the UK amid the death and destruction of war. So begins the latest update in The Letters of TS Eliot (Volume 10 1942-1944) edited by Valerie Eliot and John Haffenden.

The book is published by Faber and Faber, where Eliot worked as a director during the war with his friend and chairman of the company, Geoffrey Faber. Book editor Valerie Eliot, the writer’s former wife who helped collect the letters, died back in 2012 at the age of 86.

Not only was he trying to get on with his own writing, but many letters in the book reflect Eliot’s opinion of whether or not new writers’ work was suitable for publishing.

At the same time, one of his official duties at the Russell Square building during the war was a regular stint of fire watching.

He would share the all-night shift with two colleagues, according to a rota, with each member of the team putting their head down to try and sleep between duties.

“I’ve taken to sleeping in my teeth,” Eliot writes, describing his stress at trying to sleep fully clothed in case of an emergency and referring to himself as a “wambling old codger”. He also confided to a friend: “I don’t like clambering out on roofs, and I was always afraid I should have to tackle a fire-bomb in some dizzy place.”

One night in June 1944 a missile – one of the first of the V-I bombs, known as buzz bombs or fly bombs – hit the middle of Russell Square. It demolished a brick pagoda and shattered the front windows of the Faber offices and brought down some of the ceilings.

Luckily neither Eliot nor Geoffrey Faber was in the building and no one was injured.

American-born Thomas Stearns Eliot was famous for many poems and plays including The Waste Land in 1922, The Four Quartets, 1942, and Old Possums Book of Practical Cats, 1939, which inspired Andrew Lloyd Webber’s musical Cats, which has run for 21 years. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for modern literature in 1948.

A spiritual man who was Anglo Catholic, his influence and so-called power resulted in a jolly nickname: The Pope of Russell Square.

Among writers he did accept into the Faber fold were Lawrence Durrell, Henry Treece, Roland Duncan and Anne Ridler. But not George Orwell. We read his polite letter to Orwell written July 13 1944.

“I know that you wanted a quick decision about Animal Farm: but the minimum is two directors’ opinions, and that can’t be done under a week.”

Eliot goes on to explain to Orwell that his is a “distinguished piece of writing and skillfully handled with a narrative that keeps one interested –and that is something very few authors have achieved since Gulliver.”

Eliot explains: “We have no conviction (and I’m sure none of the other directors would have) that this is the right point of view from which to criticise the political situation at the present time.”

Eliot also turned down drama director Joan Littlewood who offered a play written by her husband Ewan MacColl on the grounds that he didn’t think he was qualified to criticise it.

Eliot had happier moments. He particularly enjoyed visits to his office by American servicemen who were genuinely keen for cultural conversations and beer drinking.

“He enjoyed their company,” Haffenden writes, “and he was gratified to discover that mercifully few of the GIs brought portfolios of their poems for his opinion.”

Perhaps one of the most entertaining parts of the book is the letters by Eliot to his friend John Hayward.

Hayward was wheelchair-bound with muscular dystrophy and Eliot’s initial motivation for sending Hayward regular newsy missives was to relieve his friend’s loneliness.

Eliot writes to Hayward on December 15, 1943, that he’d been away for week to a small clinic where he was treated for the flu.

“This topical flu is very unpleasant while it is at its height, and I hope you won’t succumb to it. If so, it is really worth the 12 guineas to be put away for a week. Three or four nights of changing sweat-soaked pyjamas reduce one’s weight too much. The only out about this nursing home, otherwise excellent, is that it is a converted quaint cottage, and there was another patient, recovering from double pneumonia, in a room which could only be reached by passing through mine.”

Haffenden writes: “In truth, they had much in common, loved to share jokes and to engage in a running commentary on friends and foes, and on current affairs.”

Eliot died aged 75 in 1965.

• The Letters of TS Eliot, Volume 10: 1942-1944. Edited by Valerie Eliot and John Haffenden. Faber & Faber, £60.