All the wave: the prolific musician whose fans included Dickens

In the latest in his series on eminent Victorians, Neil Titley considers Henry Russell

Friday, 10th October 2025 — By Neil Titley

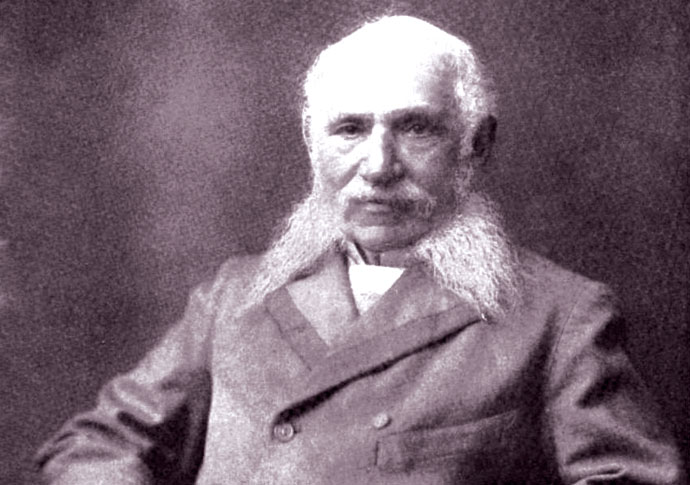

Henry Russell

THE past 60 years have been a prolific period for British singer-songwriters – Paul McCartney is credited with about 500 solo compositions; Elton John with around 575; and David Bowie with over 700. However, with more than 800 songs to his name, Henry Russell (1812-1900) was a noteworthy predecessor.

Born in Sheerness on the Isle of Sheppey, Henry was the great-nephew of the Chief Rabbi Solomon Hirschel, (his father having changed his name from Levy to Russell.)

The family soon left Kent and moved to the London slum area of Seven Dials, where Henry studied music and joined a children’s opera.

When this group performed before George IV at the Brighton Pavilion, the King was “so delighted that he took Henry on his knee and kissed his cheek”.

This royal patronage failed to deliver much pecuniary advantage though and, aged 10, Henry was sent to work in a chemist’s shop. He proved to be an inept apprentice and later recalled giving a customer who asked for Epsom salts with “enough poison to kill 50 persons”. The mistake was corrected in time to prevent Henry becoming better known as a mass murderer than as a songwriter.

His fortunes changed when, aged 12, he was sent to study classical music at the Bologna Conservatory in Italy under the tutelage of the renowned Gioachino Rossini.

Incidentally, while in Parma in his later teens, he became involved in a boxing bout with another young Englishman with whom he exchanged bloody noses. His opponent later became famous during the Crimean War as the Captain Lou Nolan, whose muddled message caused the Light Brigade to launch its infamous Charge at Balaclava.

Aged 20, Russell set off to seek his fortune in the New World. He struggled to find work in Toronto and moved on to New York where his attempts to compose pieces for the Olympic Theatre were met with what he described as “jealousy and opposition”. To make ends meet, he became the organist at a nearby Presbyterian church. It was there that he discovered that if you speeded up sacred music, it could appeal to the secular market. For example, the stately Old Hundredth psalm, if played very fast, was ideal as the music for Get Out of de Way, Ol’ Dan Tucker. He decided to abandon classical work to concentrate on ballads.

During the 1830s Russell found success performing one-man concerts across North America. Although his real circuit was in Canada and the American eastern seaboard, he once travelled to the (then very) Wild West to listen to native American Indian music. After a horrible journey through the trackless prairie, Russell met the tribesmen. He was unimpressed by their musical skills: “Their yelling was truly fearful. It was just hideous noise.”

When he eventually staggered back to St Louis, he reported that it had been “a hellish trip just to hear a few men howling”.

On a similar visit to the prairie in 1833, a Scottish friend of Russell’s found his party surrounded by wolves. The terrified group huddled around the fire and tried to keep the wolves at bay by throwing out cheese and pickle sandwiches. As their supplies ran out, the party gave themselves up for lost.

Then the Scotsman had an idea. As he told Russell: “I picked up ma bagpipes and started to give the wolves a bit of a fantasia. Och, mon, ye should have seen the beasties flee.”

Returning to England in 1841, Russell used his popularity and the content of his songs to raise awareness and funds for such causes as the anti-slavery movement and the Relief of the Irish Famine for which he collected £7,000.

As Elton John was reliant on the words of Bernie Taupin, so Russell was dependent on such writers as Alfred, Lord Tennyson, William Thackeray and, above all, Charles Dickens to provide his lyrics. Dickens and Russell shared a common background in that their fathers had worked in the dockland communities of Kent and they both held strongly liberal views. In particular, Dickens admired Russell’s support for the reform of the dreadful conditions inside Victorian mental asylums. He said that Henry’s song The Maniac “had done as much in exposing this great social evil as any of my own writings”.

In a lighter moment, Russell also wrote the music for Dickens’ songs in The Pickwick Papers.

After the lyricist Epes Sargent had been inspired by watching ships in New York harbour, he offered the words of A Life on the Ocean Wave to Russell. The pair went immediately into a Broadway music store where Henry, sitting at a display piano, picked out “the melody that seemed to be floating in my brain”. The song became an immediate hit. Russell dedicated it to another friend, the American novelist Fenimore Cooper.

Russell died at 18 Howley Place, Maida Vale, and his remains are interred in Kensal Green Cemetery.

In 1889 the British Admiralty authorised the use of A Life on the Ocean Wave as the regimental march of the Royal Marines.

• Adapted from Neil Titley’s book The Oscar Wilde World of Gossip. See www.wildetheatre.co.uk. Available at Daunts, South End Green