A test of character?

Francis Beckett explains how writing a play can sometimes get a writer nearer to the truth

Thursday, 9th February 2023 — By Francis Beckett

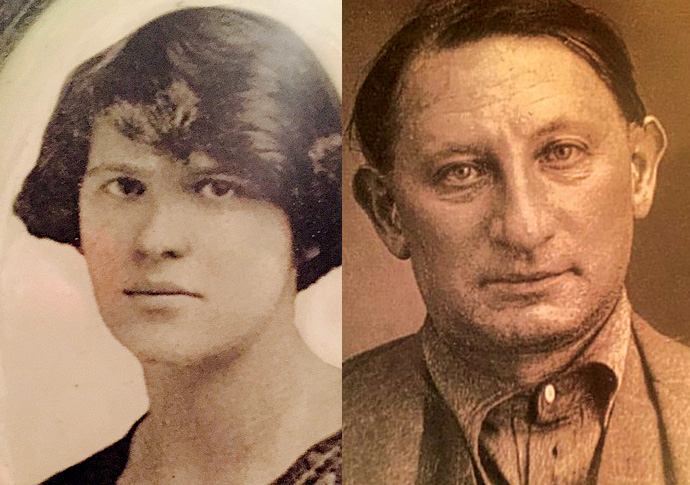

Rose Cohen, and Max Petrovsky’s prison photograph [Michael A Petrovsky]

A QUARTER of a century ago, I heard a story that has haunted me ever since. Only now have I found some sort of explanation – and I don’t know if it’s the right one.

I was researching a book about British communism in the Marx Memorial Library, a beautiful period building on Clerkenwell Green, and a Mecca for historians of the left.

At my table sat an elderly woman who introduced herself as Joyce Rathbone, and told me she was reading up on her aunt, Rose Cohen.

The name meant nothing to me, and she explained.

Rose was a bright star of left-wing politics after the First World War: a suffragette, a journalist with a growing reputation, an effective socialist campaigner, and, eventually, an agent of the Communist International (Comintern), carrying Soviet money and instructions secretly to Communist parties all over the world.

Rose married fellow Comintern agent Max Petrovsky, and they settled in Moscow and had a baby – just in time for all three of them to be caught up in Stalin’s purges.

Max and Rose were arrested. Their baby was wrenched from her arms and sent to an orphanage.

She was far from being the only Londoner caught up in the purges. There was Pearl Rimel, who worked at the then newly built Black Cat cigarette factory, the wonderful art deco building in Hampstead Road, Camden, until she went to Moscow with her Dutch communist husband.

There was Freda Utley, who had been a research fellow at the London School of Economics, and went to Moscow with her Russian husband.

But what made Rose’s story different, and far more puzzling, was that the leading British Communist Harry Pollitt had was so passionately in love with her when they were both young that he proposed marriage to her, on his own account, 14 times.

Yet when she was arrested, Pollitt, by then the leader of Britain’s communists, said nothing. Privately, he seems to have made representations to Stalin, but publicly he attacked reports of her treatment as anti-Soviet smears.

What an appalling betrayal! Yet my reading of Pollitt is that he was not a bad man. Like his views or hate them, he was genuinely outraged by the poverty and injustice he saw around him and had experienced in his childhood, and devoted his life to trying to end it, in what he honestly believed was the most effective way.

How could such a man have stayed silent while the woman he has so desperately loved was rotting in a Soviet jail?

I put Rose’s story, alongside the stories of Pearl Rimel and Freda Utley, in a book called Stalin’s British Victims.

The book described the events, but it didn’t have an answer to my question.

So I turned it into a play which I called Vodka with Stalin. Writing drama, you can crawl inside the skin of your characters, without worrying about what you can’t prove.

You can invent what might have been said at unrecorded meetings, for example between Harry Pollitt and Stalin. You can invent meetings, just to see what might have been said. And through all this invention, a greater truth sometimes emerges.

Now I think I have some idea what happened to Harry Pollitt. I remembered going to the Mary Fielding Guild in Highgate Hill to see Pearl Rimel’s sister Hetty Bower, then 98, with a razor-sharp mind and perfect recall.

Hetty’s communism never wavered, even though she understood that dreadful things had been done in its name.

Pollitt, I think, went a stage further. He was sure that a few dreadful things would happen on the road to the revolution, but it was worth it, because the prize was a better life for the mass of the people.

This belief was tested in the most heartbreaking way. Did Harry think that sacrificing the woman he loved was a test of his character?

He would not be the first political leader to make that mistake. You find it on the right as often as the left. Look, for example, at poor, deluded Liz Truss, who is still sure that if she had been allowed to run down public services even further, and hand even more wealth to the richest people, the masses would benefit eventually. And that prize was worth exposing some people to appalling poverty.

• Vodka with Stalin is at Upstairs at the Gatehouse,1 North Road, N6 4BD from Feb 15-18. Details at. www.upstairsatthegatehouse.com or phone 020 8340 3488.